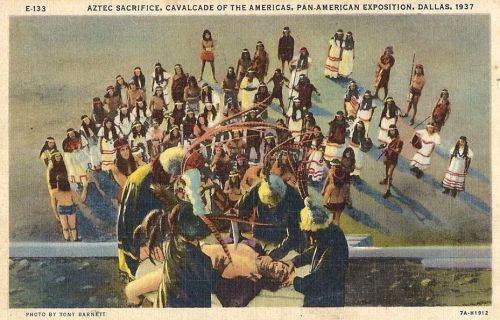

Aztec sacrifice with a warrior, not a virgin, on the official postcard

Aztec sacrifice with a warrior, not a virgin, on the official postcard

by Paula Bosse

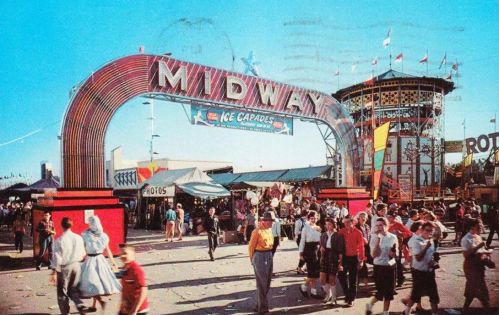

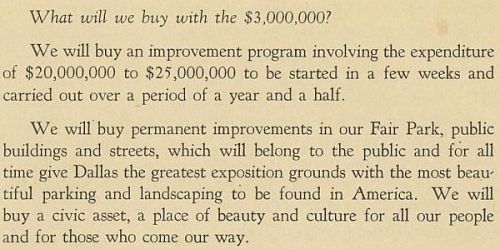

The Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition at Fair Park was a four-and-a-half-month extravaganza which opened in June, 1937 as a follow-up of sorts to the previous year’s Texas Centennial Celebration. According to promotional material, its goal was to celebrate the Americas and “to promote the feeling of international goodwill between the twenty-one independent nations of the New World.” (It was also hoped that the city could rake in some more Centennial-sized cash.)

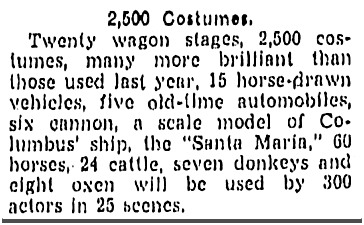

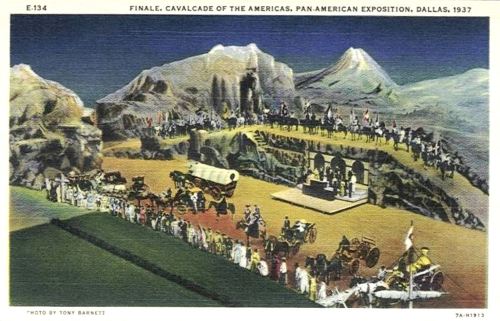

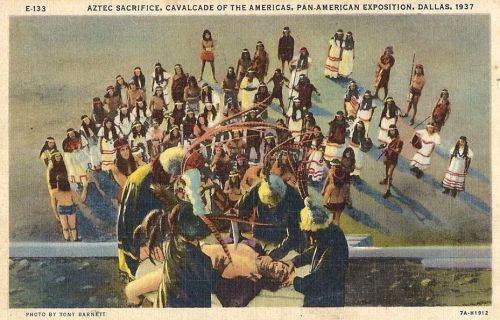

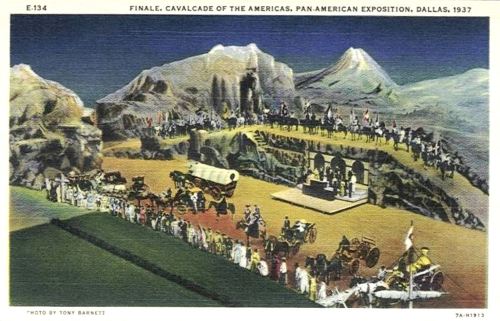

One of the biggest attractions of the Pan-American Expo was a huge production called Cavalcade of the Americas, which presented highlights from the history of Latin America and the United States. There were scenes from ancient Mexico, Columbus’ landing, the Revolutionary War, Stephen F. Austin’s arrival in Texas, the settling of the Old West, etc., right up to FDR’s participation in the Inter-American Peace Conference in Argentina in 1936. Utilizing much of the same infrastructure as the previous year’s Cavalcade of Texas, it was staged outdoors, in the old racetrack, with a 300-foot stage and elaborate scenery depicting an ocean, mountains, and a smoking volcano. Horses, wagons, “ships,” and a cast of hundreds took part in the production.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

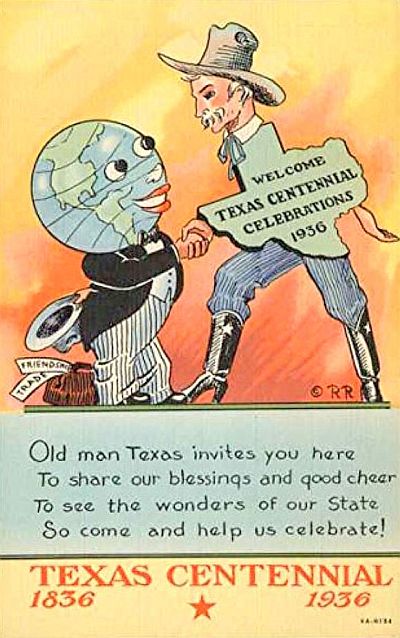

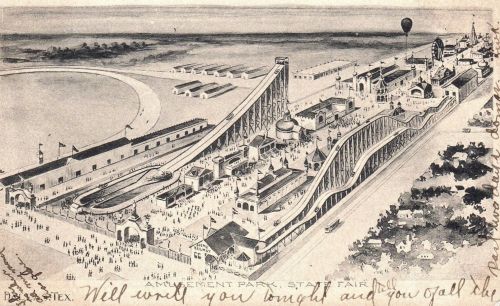

It was quite elaborate. The postcard view below will give you an an idea of the scale of what was being billed as the world’s biggest stage.(I believe the whole thing revolved — or at least part of it did — with another stage on the side facing away from the audience; the scenery, cast, and perhaps the donkeys, would change out before revolving to face the audience.)

The opening scene featured an Aztec sacrifice and an angry volcano. Start big! This relatively brief portion of the show caused a lot of headaches (and/or much-welcomed publicity) for the producers, State Fair organizers, and, probably, the image-conscious Dallas Chamber of Commerce. But why? As originally written (by the remarkably prolific Jan Isbelle Fortune), the Aztec sequence involved the sacrifice of a struggling young maiden atop a blood-stained pyramid. Two months before the opening of the Expo, a rather sensationalistic photo of this historical reenactment appeared in the pages of newspapers across the country, no doubt resulting in raised eyebrows and whetted appetites. (Click to enlarge!)

Greencastle (Indiana) Daily Banner, 1937

Greencastle (Indiana) Daily Banner, 1937

The star of this scene was 17-year-old Geraldine Robertson, who had been crowned Queen of the Centennial the previous year and who played a multitude of roles in the current production, including Cortés’ “lover and interpreter,” a young woman in a Boston Massacre scene, Martha Washington, and the wife of Jim Bowie. Here she is in real life in 1936, with Jean Harlow platinum-blonde hair, posing for one of a seemingly endless number of publicity photos.

Geraldine Robertson, 1936

Geraldine Robertson, 1936

And the thing that caused so much trouble? Probably not what you would assume.

Before the Exposition opened, the Dallas-based Mexican Consul, Adolfo G. Dominguez, became aware of this casting choice. And that was when the mierda probably first hit the ventilador. Dominguez was adamant that the virgin be replaced with the more historically accurate male warrior. He probably said much the same thing to the Cavalcade producers when confronting them about his concerns before the Expo began as he did when he said this in a Dallas News article on the topic weeks later:

“We Mexicans feel that use of a girl in the role can bring nothing but racial prejudice and misconception of the true meaning of the Aztec human sacrifice as it was performed, not thousands of years ago, as has been wrongly represented, but as late as 1521.” (DMN, July 28, 1937)

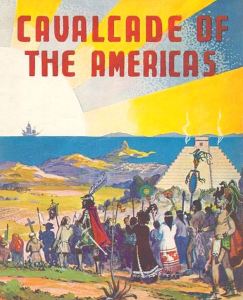

The producers acquiesced, and when the Exposition began its run on June 12, 1937, the opening scene of the Cavalcade did, in fact, feature a sacrificial warrior. But on Sunday, July 25, the producer of the extravaganza brought the scantily-clad virgin back and nixed the warrior, hoping the added sex appeal and pizzazz would increase audience numbers. (Interestingly, when the Exposition opened, tickets to Cavalcade of the Americas cost 50⊄ — about $8.00 in today’s money — but on July 18, it was announced that, except for 600 reserved seats, admission to the show would be free. Promoters said this was being offered as a gesture of goodwill to Expo visitors, but one wonders if they weren’t having a hard time filling the 3100-seat grandstand.)

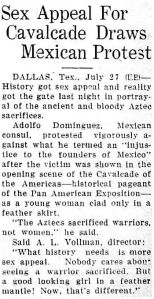

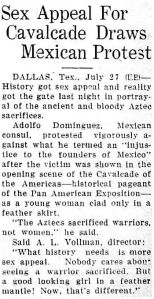

Señor Dominguez was not amused by this sexed-up revamping and protested. A. L. Vollman, the Cavalcade’s producer-director pooh-poohed the diplomat’s protestations and responded in true impresario fashion: “What history needs is more sex appeal.” That didn’t go over particularly well with the consul, who thought he’d already dealt with the problem weeks before. (Click to see larger image.)

Waxahachie Daily Light, July 27, 1937

Waxahachie Daily Light, July 27, 1937

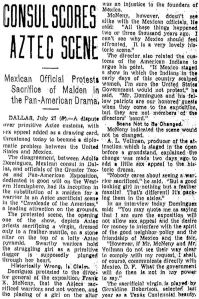

Dominguez complained to Frank K. McNeny, Director General of the Exposition, saying that the scene was historically inaccurate and was an injustice to the founders of Mexico. McNeny disagreed, saying that the scene involving the plunging of a dagger into the breast of a sacrificial virgin was “a very lovely historic scene.” He declined to bring back the warrior, because, as Vollman noted, the revamping had increased attendance: “It’s packing them in the aisles.” An exasperated Dominguez said that if the change from maiden back to warrior was not made, he would take the matter to the Mexican government.

FWST, July 28, 1937

FWST, July 28, 1937

At this point, a disagreement over the gender of a character in what was, basically, an oversized school history pageant was dangerously close to setting off an international incident. It was also causing embarrassment for local civic leaders who were looking upon the Exposition as a major marketing tool for the city as well as a symbolic display of Pan-American solidarity and goodwill. Can’t we all just get along, amigo?

The refusal of the Cavalcade to UN-revamp the show did not deter the Mexican Consul who, by now, was probably more het-up than ever. Dominguez decided to go over McNeny’s head. He pulled out the written agreement he had made with fair officials back in the spring — which clearly stated that a male warrior and NOT a young woman would feature in the theatrical human sacrifice — and he took it to the top man, State Fair president Fred F. Florence. Florence discussed the matter with his board of directors who voted “to a man” to uphold the original agreement.

The warrior would be reinstated as the writhing victim on the bloody sacrificial stone. The sexy maiden would have to hand over the 30-foot-long robe, which had been made from 9,000 feathers and which had trailed behind her as she was carried up the great pyramid at Tenochtitlán. The actor playing the warrior was probably happy to get back in the spotlight. Geraldine Robertson, the virgin who had trailed that robe, was relegated to a role as a daughter of Montezuma.

Presumably the dagger kept plunging into the flailing warrior’s heart twice nightly for the remainder of the show’s run, and the memory of that short-lived international squabble was quickly forgotten (…until now).

And they all lived happily ever after. / Vieron felices por siempre.

*

Hey! If you’ve read this far, here’s a little reward. A Universal Newsreel titled “Pan-American Exposition Is Opened For 1937, Dallas, Tex.” — which contains 20 whole seconds of the Aztec (warrior) scene! — can be viewed on the T.A.M.I. (Texas Archive of the Moving Image) site, HERE. The entire short newsreel is interesting (sadly, it has no sound), but if you want to jump to the sacrifice scene, it begins at the :49 mark. (If you’re watching on your desktop, make sure to click the little square just to the left of the speaker icon beneath the viewing area to watch it full-screen.

Super-grainy screenshot from the Universal newsreel, 1937

Super-grainy screenshot from the Universal newsreel, 1937

***

Sources & Notes

Postcards of the Pan-American Exposition are from “the internet.”

Color souvenir program image from the Watermelon Kid site; background on the Pan-American Exposition can be found on the same site, here.

All other clippings as noted.

Related Dallas Morning News articles:

- “As Sacrificial Virgin, Star of Cavalcade Put In Showy Opening Act” (DMN, July 26, 1937)

- “Cavalcade Dispute Is Won by Consul As Virgin Is Replaced” (DMN, July 28, 1937)

Below, an interview with Jan Fortune on her Cavalcade of the Americas; it appeared in her hometown newspaper, The Wellington (Texas) Leader on March 18, 1937. She also wrote the Centennial’s big production, Cavalcade of Texas, the previous year, in 1936.

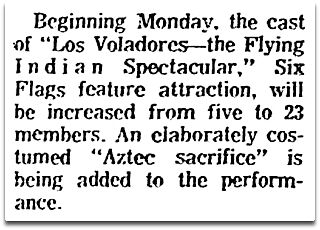

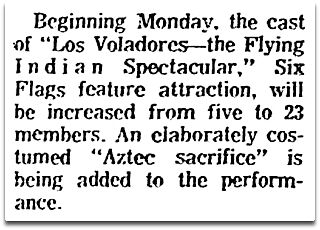

And, speaking of Aztec human sacrifices in DFW (a phrase I don’t believe I’ve ever written…), the following tidbit was contained in an article about Six Flags Over Texas’ 1970 season.

FWST, May 21, 1970

FWST, May 21, 1970

Promotional material about Los Voladores — a group of aerialists from Mexico — informs us that in their show “a beautiful maiden’s life is given as tribute to Tlaloc, the rain god.” Those beautiful maidens can’t catch a break. Sorry, Adolfo.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

FWST, May 21, 1970

FWST, May 21, 1970

DMN, Oct. 20, 1912

DMN, Oct. 20, 1912