The 67-80 Split Near Mesquite — ca. 1951

Far East Dallas (click for VERY LARGE image)

Far East Dallas (click for VERY LARGE image)

by Paula Bosse

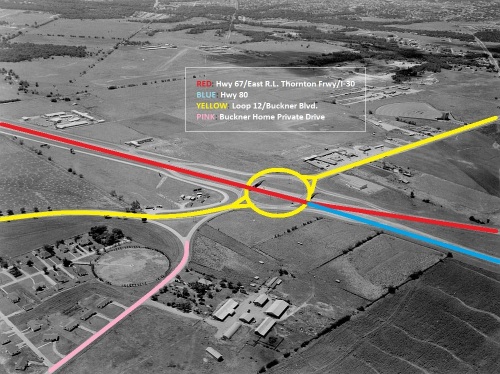

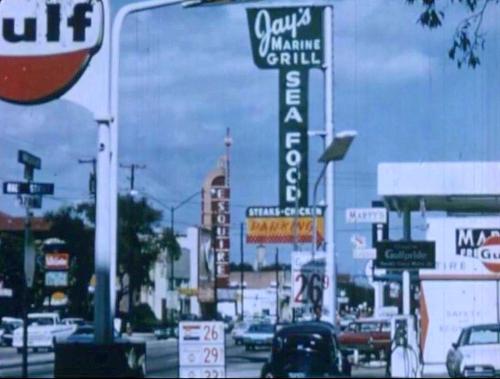

Above, a wonderful photo showing Highway 67 (now East R. L. Thornton Freeway and I-30) splitting off into Highway 80, just east of Loop 12/Buckner Blvd., surrounded by lots and lots of open land. At the top right, along Buckner, you can see the Buckner Drive-In, above it the original location of the Devil’s Bowl Speedway, and farther over, to the left, White Rock Airport. Part of the sprawling property belonging to the Buckner Orphans Home can be seen at the bottom left. Today, this is right about at the Dallas/Mesquite border. Except for the highways, this is pretty unrecognizable today!

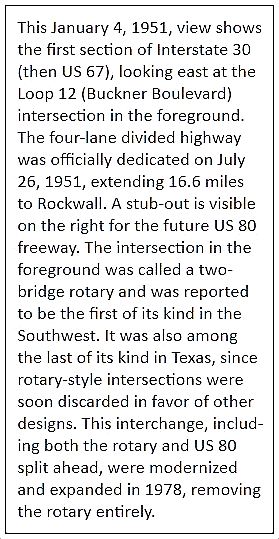

Here is a second photo, dated Jan. 4, 1951, with Oscar Slotboom’s caption below (from Slotboom’s exhaustively researched book and website, Dallas-Fort Worth Freeways).

*

The Buckner Orphans Home was founded in 1879; it was both a home for orphaned children and a working farm, and at its height, it occupied some 3,000 acres of land (!). Take a look at a 1911 photo here to give you an idea of the size of the place. The buildings seen at the bottom left of the photo above were houses used by Buckner staff; the Home itself is out of frame.

White Rock Airport opened about 1941 and was in use until 1974. Here is a photo of it soon after it opened.

(Several more photos and memories about this airport can be found here.)

Devil’s Bowl Speedway opened in March, 1941. If you wanted to see jalopy races, you headed to Devil’s Bowl. (DBS is still around, nearby, at a different location.)

The Buckner Boulevard Drive-In opened on June 4, 1948. It was the first drive-in in Dallas to have individual car speakers that one placed in one’s car. (More on the Buckner Drive-In can be found at Cinema Treasures, here.)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo is from the TxDOT Photo Files and can be viewed on the Texas State Archives’ Flickr page, here; the date is given as “circa 1940,” but as the drive-in didn’t open until 1948, the date of the photo is probably closer to 1950. (The second aerial photograph — from Oscar Slotboom’s fantastic Dallas-Fort Worth Freeways — is dated 1951, so I’ve updated the title of this post.)

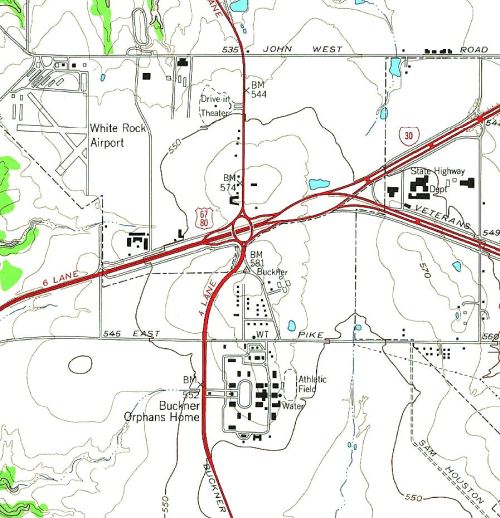

Thanks to Mark’s comment below, I’ve found this detail of a 1957 topo map from the United States Geological Survey. It’s a few years after the photo above was taken, but it shows the layout of the Buckner Children’s Home more fully. (The east-west highway called “East Pike” here is now known as Samuell Blvd.) Click map for larger image.

The Dallas/Mesquite city limits boundaries have moved over the years, but a current view of the boundary — which involves the area seen in this photo (seriously, this exact area) — can be seen here.

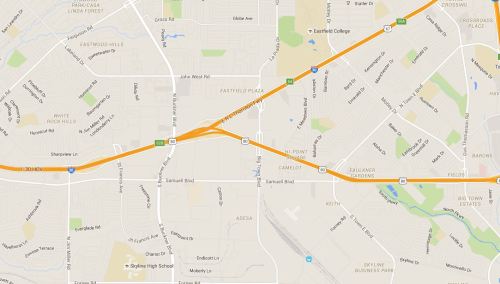

Below, a current Google Maps view of this interchange:

And, if like me, you need some helpful guidance:

Thanks to members of the Dallas History Facebook group for helping me figure out what I was looking at, especially David and Chuck — thanks, guys!

Click pictures and articles for larger images.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

FWST, Nov. 3, 1924

FWST, Nov. 3, 1924 FWST, Nov. 11, 1924

FWST, Nov. 11, 1924