El Panamericano (click for larger image) (Villasana)

El Panamericano (click for larger image) (Villasana)

by Paula Bosse

In 1937, Joaquin José (J. J.) Rodriguez opened the first theater in Dallas to show Spanish-language movies. It was the Azteca, at 1501 McKinney Avenue, one block away from the still-there El Fenix. He soon changed the name to the Colonia and later to El Patio.

1938 city directory

1938 city directory

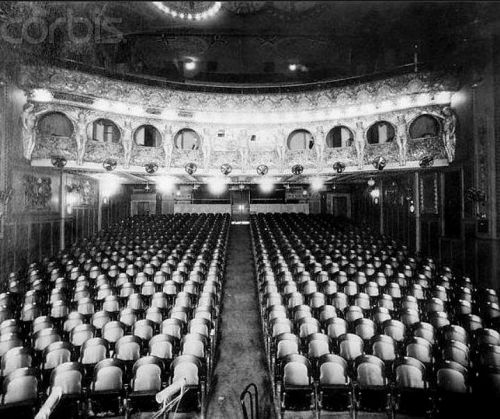

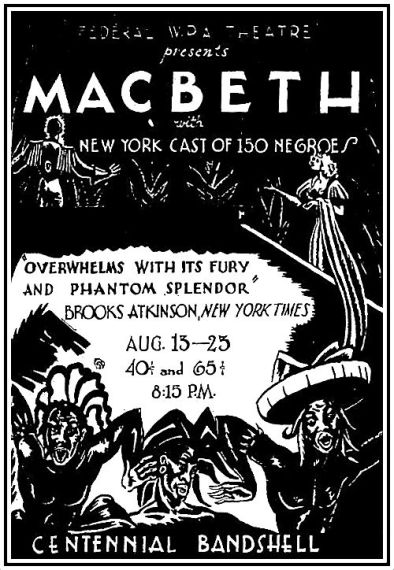

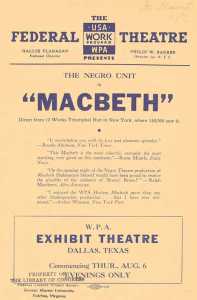

Even though a journalist later described this theater as being “dingy” and “unprepossessing” (DMN, July 31, 1944), the theater was quite successful, little surprise as the Hispanic community of the day was sorely underserved in almost every way. This endeavor was so successful that in the fall of 1943, the 36-year old entrepreneur made a big, BIG move: he bought the stunning and palatial Maple Avenue building that once housed the famed Dallas Little Theatre, an amateur theatrical group that had burst on the scene in 1927, but which had fallen on hard times in recent years.

1930s

1930s

Rodriguez raised the necessary $35,000 (equivalent to almost half a million dollars in today’s money), bought the beautiful building at 3104 Maple, and renamed it Teatro Panamericano. The angle of the article that appeared in The Dallas Morning News on Sept. 22, 1943 announcing the new theater had the new moviehouse as being a boon to students and Anglo members of the community who might need to brush up on their Spanish rather than as a welcomed entertainment venue for the “Mexican colony” living and working in the adjacent Little Mexico neighborhood.

El Panamericano was an immediate success and soon became not only a place to see movies, but also a place for Dallas’ Spanish-speaking community to meet and mingle, with PLENTY of room for all sorts of events. (It was so big that Rodriguez and his family lived in back. He also had TWO offices and more storage space than he had things to store in it. No skimping on the parking lot either — one ad touted an acre of parking space.)

The theater’s importance to the Hispanic community of Dallas was both cultural and social:

For Mexican-Americans growing up in Dallas during the ’50s and ’60s, the films at El Panamericano, were a link with their historical and cultural heritage. For some, it would be their only exposure to cultural ties; for those whose families were stressing their Americanization by using only English in the home, it was a chance to practice their Spanish. (“Festival Fades, but Mexican Movies Thrive,” DMN, Aug. 9, 1981)

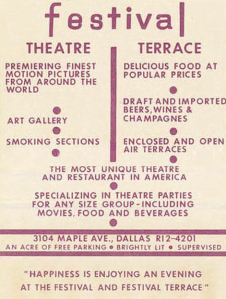

After more than 20 years of running a successful theater that catered to his core niche audience, Rodriguez was persuaded to change the theater’s focus. Mexican families had slowly moved out of the neighborhood, many to Oak Cliff where the Stevens Theater on Fort Worth Avenue had begun showing Spanish-language movies in the early ’60s and had siphoned off a large portion of Rodriguez’s audience. In 1965 the Panamericano became an arthouse cinema which showed mostly subtitled European films (and, later, underground and cult movies) — these were movie bills which were clearly aimed at college students and an upper-class Anglo audience. The Panamericano became the splashy Festival Theatre.

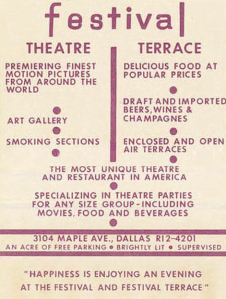

BoxOffice magazine, Nov. 22, 1965

BoxOffice magazine, Nov. 22, 1965

An indoor-outdoor restaurant — the Festival Terrace — was added, and it boasted of being “the only theater in the history of Texas with a wine and beer license.”

BoxOffice magazine, Nov. 22, 1965

BoxOffice magazine, Nov. 22, 1965

1960s (Villasana)

1960s (Villasana)

As impressive as the Festival and its array of films were, the theater struggled, and Rodriguez later called this period a “big mistake.”

“As soon as I could, I changed it back to the way it was before. In fact, I lost money on that deal.” (DMN, Aug. 9, 1981)

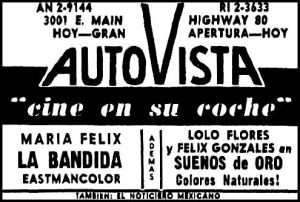

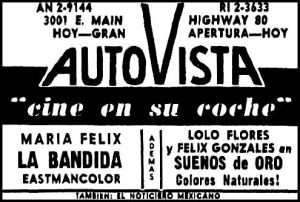

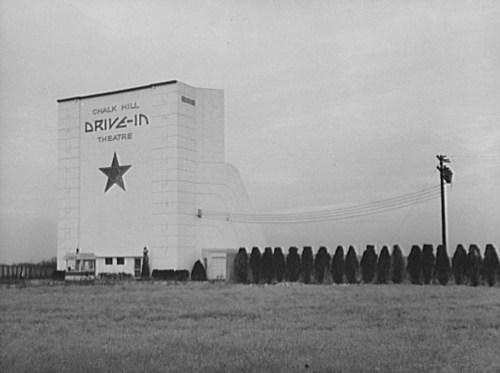

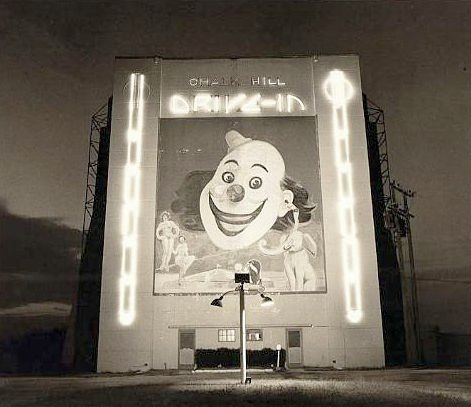

Another unusual misstep for Rodriguez at this time was his decision to open a drive-in that showed only Spanish-language films. What sounded like a great idea was another surprising failure for Rodriguez. Despite its non-stop advertising in the first half of 1965, the wonderfully-named Auto-Vista (located in Grand Prairie) lasted less than a year.

“Cine en su coche”! (March, 1965)

“Cine en su coche”! (March, 1965)

Rodriguez’s new-old Spanish-language theater — now the Cine Festival — was still popular, but it never regained its former glory. Rodriguez retired in 1981 and sold the property. Despite efforts by preservationists to save the beautiful Henry Coke Knight-designed building, it was demolished a few months later — in early January, 1982 — in the dead of night under cover of darkness (… that happens a lot in Dallas…). A nondescript office building was later built in its place.

J. J. Rodriguez died in 1993 at the age of 86, almost exactly 50 years after opening one of the most important entertainment venues for Dallas’ Hispanic population. He was a respected leader in the community and was for many years president of the Federation of Mexican Organizations, an organization he helped found in the 1930s. His theater was both culturally important and beloved by its patrons.

*

J. J. with daughter and wife (Pampa News, July 30, 1944) AP photo

J. J. with daughter and wife (Pampa News, July 30, 1944) AP photo

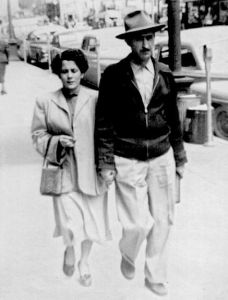

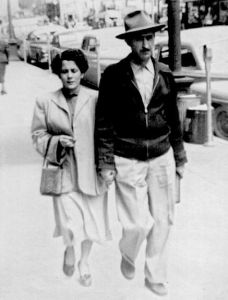

With his wife, Maria, downtown 1940s (Villasana)

With his wife, Maria, downtown 1940s (Villasana)

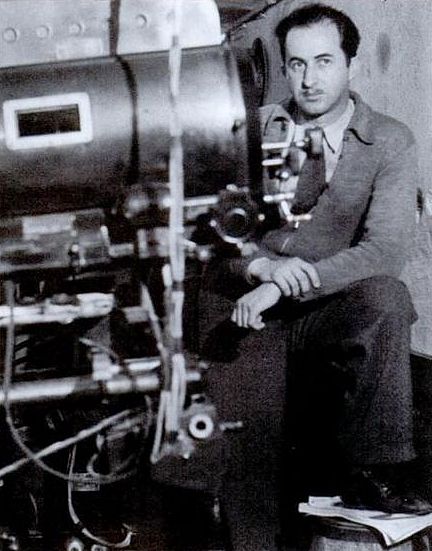

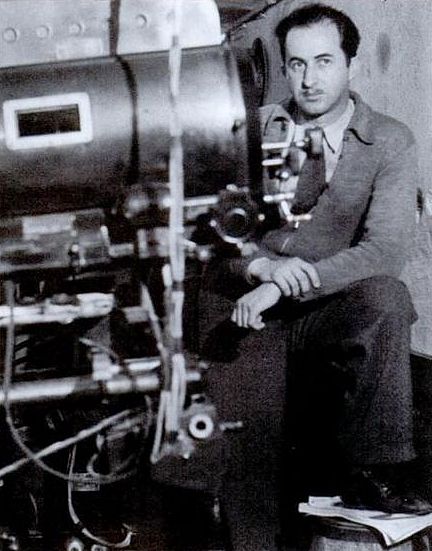

In the projection booth, 1950s (Villasana)

In the projection booth, 1950s (Villasana)

*

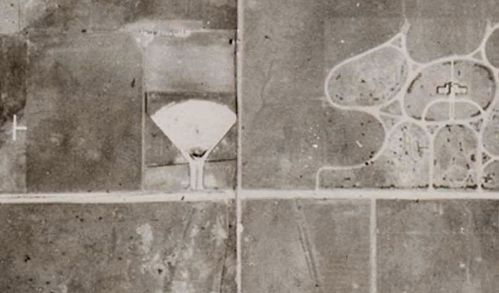

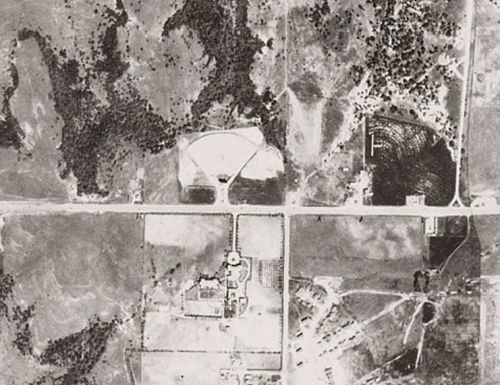

The matchbook cover image below gives an indication of how large the theater was. The building at 3401 Maple — at the corner of Carlisle, across Maple from the Maple Terrace — was gigantic.

Matchbook via George W. Cook Collection, SMU

Matchbook via George W. Cook Collection, SMU

In a Dallas Phorum discussion (here), the space was described thusly:

It was an interesting building with an outdoor terrace restaurant, a full proscenium stage, rehearsal space downstairs below the stage, dressing rooms, shop/storage areas, and even a puppet theatre built into a wall in the balcony lobby area.

To see what the corner of Maple and Carlisle looks like now, click here (have a hanky ready). Can you imagine how wonderful it would be to still have that elegant building and still see it in use as a theater and restaurant?

**

In what may well be research overkill, I thought it was odd that there was an Azteca Theatre at 1501 McKinney a year before Rodriguez owned it. I wondered if, in fact, Rodriguez had owned the first Spanish-language movie theater in Dallas, or whether that distinction belonged to Ramiro Cortez (whose name is often misspelled as Ramiro Cortes). It seems that Cortez’s theater might have featured live performances rather than motion pictures. Like Rodriguez, Cortez had ties to Dallas entertainment — read about him here.

1937 city directory

1937 city directory

***

Sources & Notes

Photos with “Villasana” under them are from the book Dallas’s Little Mexico by Sol Villasana (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011); all are from the personal collection of Mariangel Rodriguez. More photos of J. J. Rodriguez can be seen here (click “Next” on top yellow bar).

The full article from the Nov. 22, 1965 issue of the industry journal, BoxOffice, includes additional photos and information and can be seen here and here.

All other images and clippings as noted.

Articles on J. J. Rodriguez and his theaters which appeared in The Dallas Morning News:

- “Pan-American Theater to Aid Spanish Study” (DMN, Sept. 22, 1943)

- “Teatro Panamericano” by John Rosenfield (DMN, Oct. 12, 1943)– coverage of opening night festivities

- “Maple Location Regains Swank” by John Rosenfield (DMN, Sept. 18, 1965) — about the change from El Panamericano to the arthouse Festival Theater

- “Festival Fades, but Mexican Movies Thrive: Theater Owner Says Adios to Film Business” by Mercedes Olivera (DMN, Aug. 9, 1981) — about the closing of the Festival Theater

- “Encore No More” (DMN, Jan. 4, 1982) — photo of the partially demolished theater

- “Rites Set for Hispanic Leader J. J. Rodriguez — He Co-Founded Federation of Mexican Organizations” by Veronica Puente (DMN, Sept. 26, 1993) — Rodriguez’s obituary

“Dallas Theater Owner Is One-Man Pan-American Agency” — a syndicated Associated Press article by William C. Barnard — can be read here.

Read about Teatro Panamericano at Cinema Treasures, here.

Read about the competing Stevens Theater in Oak Cliff on Fort Worth Avenue, here.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

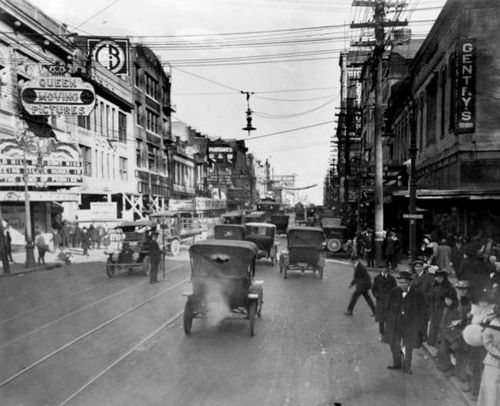

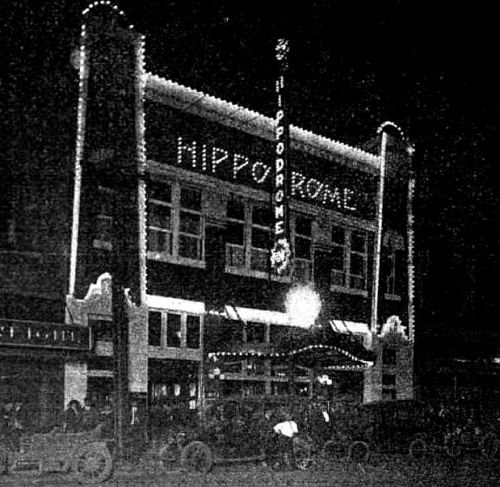

The back side of Elm, looking east…

The back side of Elm, looking east…

1938 city directory

1938 city directory

The “Cameraphone” — DMN, Oct. 19, 1908

The “Cameraphone” — DMN, Oct. 19, 1908

DMN, Oct. 20, 1912

DMN, Oct. 20, 1912

DMN, Feb. 28, 1913

DMN, Feb. 28, 1913

Dallas Morning News, May 9, 1914

Dallas Morning News, May 9, 1914 Another grainy photo, Main looking west

Another grainy photo, Main looking west