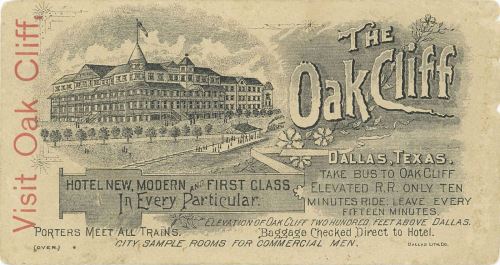

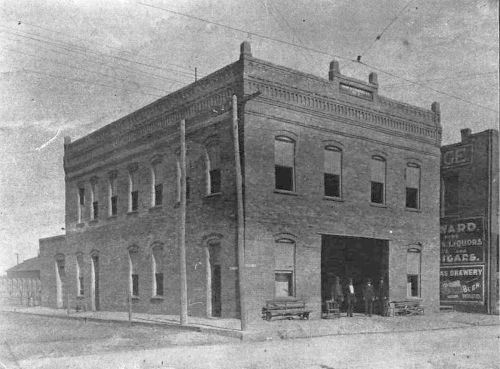

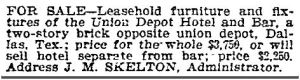

“Visit the Oak Cliff…” (click for much larger image) Photo: SMU

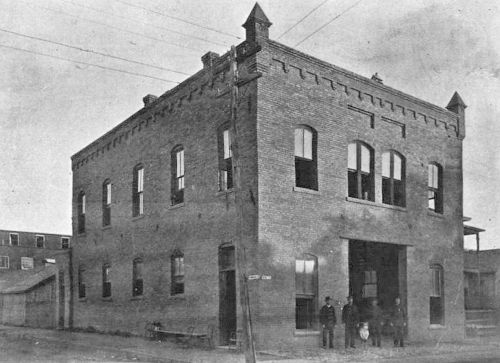

“Visit the Oak Cliff…” (click for much larger image) Photo: SMU

by Paula Bosse

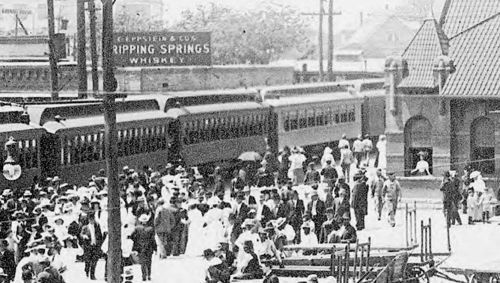

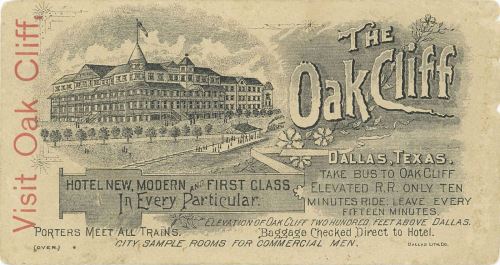

I saw this image yesterday while browsing through the George W. Cook Collection (DeGolyer Library, SMU). It’s from about 1890. It’s great. BUT, the other side of this card is even better:

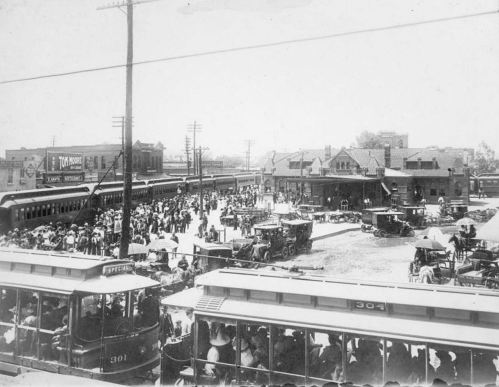

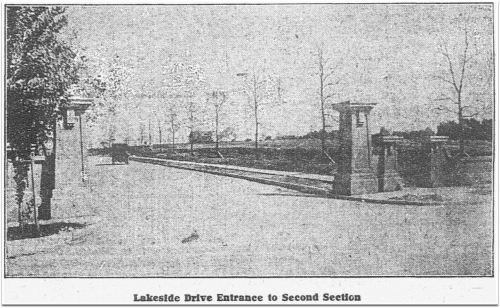

I’m not sure how realistic this drawing is, but it’s great! Oak Cliff never looked so … quaint. The best part is the depiction of the little commuter railway that Oak Cliff developer Thomas L. Marsalis built in the 1880s to handle commuter traffic between Oak Cliff and Dallas — a necessity if his development west of the Trinity was to grow. There were two little steam trains which made a complete circle and offered spectacular views of Dallas as they headed toward the river. Here’s an account of visitors from Kansas City who enjoyed their scenic ride (click to see a larger image):

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 24, 1890

Marsalis had made his fortune in the grocery business, and much of that fortune was funneled into making his vision a reality: Oak Cliff would become a large, beautiful, prosperous community. He spent huge amounts of money developing the then-separate town of Oak Cliff. A wheeler-dealer and an obsessive whirlwind, money was no object to Marsalis as he charged at full speed to make Oak Cliff a booming North Texas garden spot.

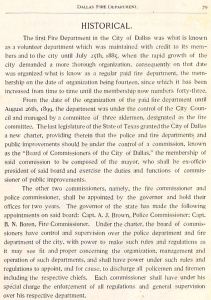

Thomas L. Marsalis — the “Father of Oak Cliff”

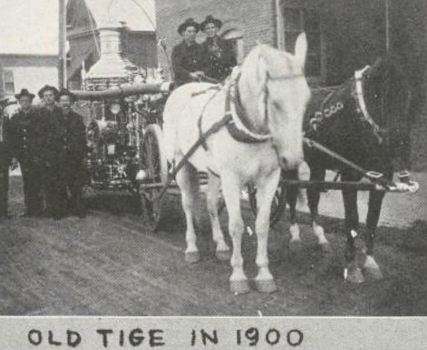

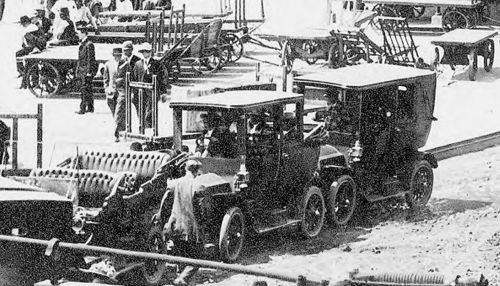

The jewel in T. L.’s O.C. crown was the 100-room resort, the Oak Cliff Hotel (which in its early planning had been called the Park Hotel). Ground was broken on Dec. 21, 1889. Projected to cost $75,000, it is said to have cost over $100,000 when construction was completed, or, over $2.6 million in today’s money.

DMN, Dec. 22,1889

A thorough description of the spectacular $100,000 showplace can be read in a Dallas Morning News article from May 25, 1890, here. When it opened on July 10, 1890, the News’ coverage of the opening included the following lyrical passage:

When darkness had settled down over the cliff the large hotel showed off to its best advantage, as at a short distance away it looked like some living monster with hundreds of fiery eyes. The lights showing from every window made a startling sight to those who coming upon it had previously seen a dark pile looming up in the night.

It was, by all accounts, a popular hotel and social gathering place. But, in November of 1891 — having been open only a little over a year — a notice appeared in the papers that the hotel would be closing for the winter for “renovations.” It never reopened. Marsalis had over-extended himself. His dreams for Oak Cliff began to dim as the stacks of unpaid bills mounted, and he found himself mired in lawsuits for the next several years. He eventually had to admit defeat, and he and his family moved to New York.

Six months after that notice of “renovations” appeared, the huge building was leased to Prof. Thomas Edgerton, who planned to open a “female seminary.”

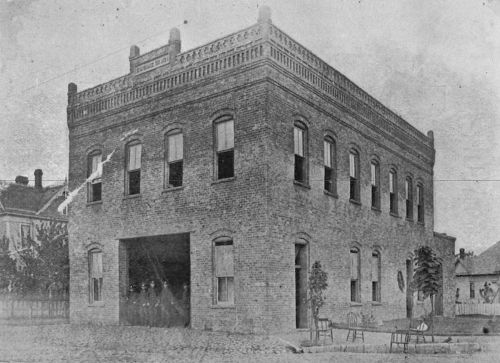

The Oak Cliff College For Young Ladies opened in the fall of 1892. And it was a spectacular-looking schoolhouse.

The college lasted until the beginning of 1899 when it changed hands and became Eminence College for a brief year and a half.

Southern Mercury, June 22, 1899

After Eminence College appears to have gone bust, the building was vacant by 1901. There was talk that Oak Cliff should purchase the property and reinstall a school, but, eventually, the building went up for auction in September, 1903.

DMN, Aug. 26, 1903

The building sold to T. S. Miller, Jr. and L. A. Stemmons for $6,850, a fraction of what Marsalis had spent building it. That’s a pretty steep depreciation.

DMN, Sept. 2, 1903

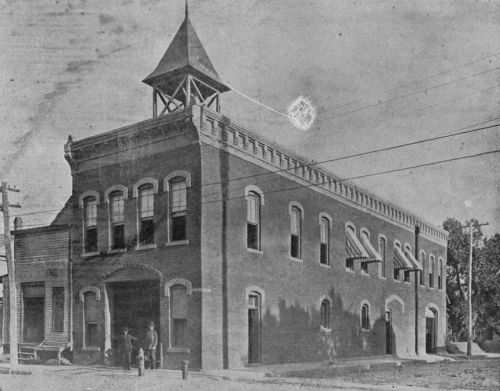

But, no fear, Hotel Cliff opened on April 18, 1904. Still looking good.

DMN, July 11, 1904

Hotel Cliff was in business through about 1915. There were some “lost” years in there when it seemed to be in limbo (during some of this time it was undergoing extensive renovation), but in 1921 it re-opened as the Forest Inn.

DMN, April 24, 1921

Bartlett News, July 4, 1924

The Forest Inn had a long run — 24 years. In 1945 the property was sold, and T. L. Marsalis’ spectacular resort hotel was demolished. It was estimated that it would take ten weeks to finish the demo job — Marsalis had spared no expense building his hotel, and it had been built to last.

The destruction is a tough job, Jack Haake, wrecking contractor, said. Despite its age, the building is so well built that much time is being required to take it apart. The lumber is of the best grade and much of it still is in good condition, Haake said. Scores of huge 2×6 planks, thirty-two feet long, were used in the building, and that timber is in excellent condition. (“Historic Oak Cliff Hotel Being Razed For New Structure,” DMN, Sept. 10, 1945)

The land apparently remained vacant until Southwestern Bell Telephone announced plans to build a three-story office building on the property in 1954; the building opened the following year. In 1986, the building was renovated and became the Oak Cliff Municipal Center, which still occupies the site.

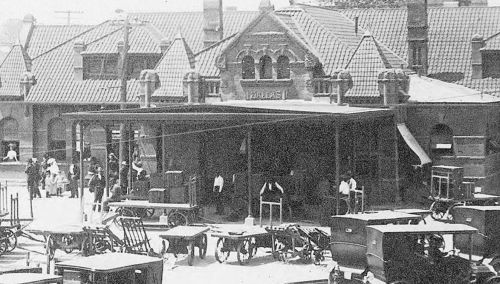

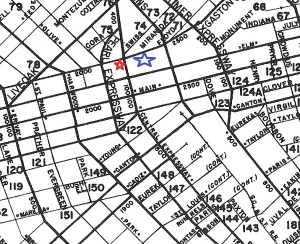

Where exactly was that huge, wonderful hotel that Thomas Marsalis built? It was located at what is now the southwest corner of East Jefferson Blvd. and South Crawford Street. A view of that corner today can be seen here. To get an idea of how much land the hotel/college once occupied, check out the 1905 Sanborn map, here (and this is after 15 years of explosive growth of Oak Cliff, so it obviously originally had much more open land around it); by 1922, encroachment was well underway, and the property was already being chopped into smaller parcels.

Google Maps

I wonder what Thomas Marsalis would think of Oak Cliff today? And I wonder what Oak Cliff would have become had Marsalis never put his money and energy into its early development?

**

There is a lot of misinformation on various online sources about the timeline of this building. As best I can determine, here is the correct chronology:

- 1889: groundbreaking for hotel, in December

- 1890-1891: Oak Cliff Hotel

- 1892-1899: Oak Cliff College For Young Ladies

- 1899-1901: Eminence College (also for young women)

- 1902-1903: vacant

- 1903: building sold at public auction, in September

- 1904-1914: Hotel Cliff

- 1914-1915: Oak Cliff College (reorganized, back for one last gasp)

- 1915-1920: basically empty, with a couple of token tenants

- 1921-1945: Forest Inn

- 1945: demolished

***

Sources & Notes

First two images show both of sides of an advertising card; “Visit Oak Cliff” is from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University — more information is here.

Photo of Thomas Marsalis from Legacies, Fall, 2007.

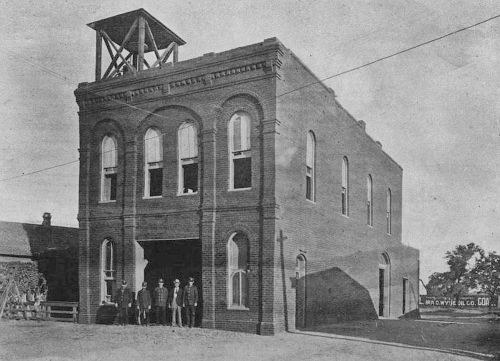

Colorized image of hotel from the front cover of The Hidden City: Oak Cliff, Texas by Bill Minutaglio and Holly Williams. The sign is hard to read, but this may show the building during the Hotel Cliff days.

The detail of an Oak Cliff College envelope comes from the Flickr page for the Texas Collection, Baylor University, here. (Sure hope Mr. Edgerton was able to get a refund on that printing job — having “Oak Cliff” misspelled on official college correspondence probably caused a grimace or two!)

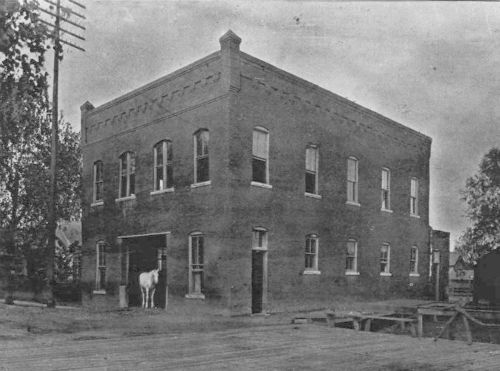

Large black and white photograph of Oak Cliff College appeared in William L. McDonald’s Dallas Rediscovered; photo from the collection of the Dallas Public Library.

Hotel Cliff postcard from the Cook Collection, SMU; information is here.

See the beautiful house Marsalis built for himself (but which he might never actually have lived in) in my post “The Marsalis House: One of Oak Cliff’s ‘Most Conspicuous Architectural Landmarks,'” here.

Thomas L. Marsalis is a fascinating character and an important figure in the development of Oak Cliff, but his post-Dallas life has always been something of a mystery. I never really thought of myself as a “research nerd” until I started this blog, but reading how a few people in an online history group pieced together what did happen to him was surprisingly thrilling. This round-robin investigation began in the online Dallas History Phorum message board, here, and finished as the Legacies article “Where Did Thomas L. Marsalis Go?” by James Barnes and Sharon Marsalis (Fall 2007 issue). If you have some time, I highly recommend reading through the Phorum comments and then reading the article. It’s very satisfying!

All images and clippings larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

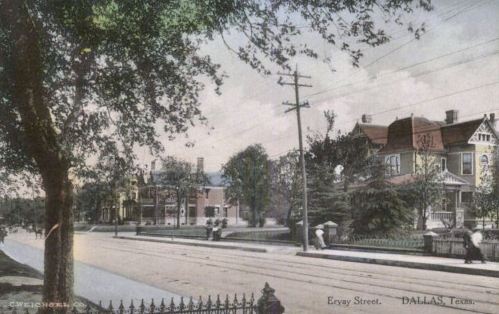

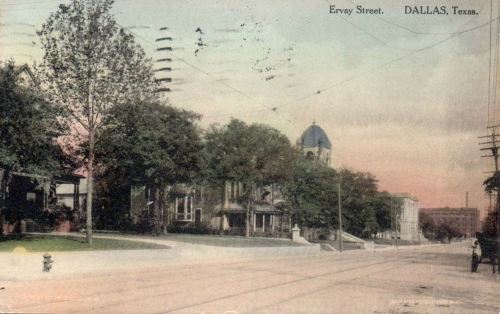

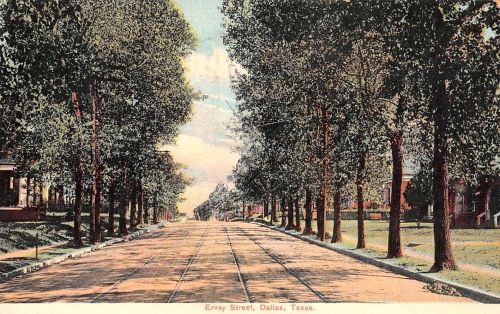

Cook Collection/DeGolyer Library/SMU

Cook Collection/DeGolyer Library/SMU