Dallas in “The Western Architect,” 1914: Places of Leisure, Etc.

by Paula Bosse

Continuing with the series of photos from the all-Dallas issue of The Western Architect, which featured photos of new buildings which had popped up all over the city between the years of about 1910 to 1914. Today, in an attempt to categorize the seven buildings in this post, I’ve decided on “places of leisure” — although one of the places is a high school, and a high school is hardly a place of leisure. Two of these buildings are still standing: one which you’ve no doubt heard of as being at death’s door for a few decades now, and the other… well, you’ve probably never seen it or been aware of it (but it’s my favorite one in this group!).

*

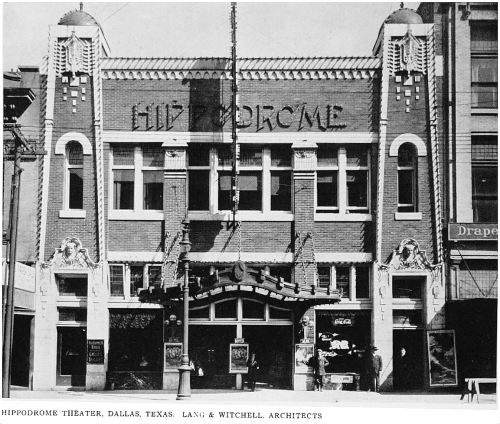

1. THE HIPPODROME THEATER (above), 1209 Elm Street, designed by architects Otto Lang & Frank Witchell. Built along Dallas’ burgeoning “theater row” in 1912-1913, the Hippodrome was one of the city’s grandest “moving picture playhouses.” Among its lavish appointments was this odd little tidbit: “Over the proscenium arch there is an allegorical painting representing Dallas as the commercial center of the Southwest,” painted by the theater’s decorator, R. A. Bennett. Below was a fire curtain emblazoned with a depiction of Ben Hur (a “hippodrome” was a stadium for horse and chariot races in ancient Greece). So that was a nice little weird culture clash. Though originally a theater which showed movies exclusively, it eventually became a theater featuring movies as well as live vaudeville acts. As the Hippodrome became less and less glamorous, it resorted to somewhat seedier burlesque acts (it was raided more than once,for employing female performers who were too scantily clad) and the occasional boxing or wrestling match. The building was sold several times and was known as the Joy Theater, the Wade, the Dallas, and, lastly, the Strand. I was shocked to learn this old-looking-when-it-was-new building stood for almost 50 years and wasn’t demolished until 1960 (that façade must have looked very different by then). (See it on a 1921 Sanborn map, here.) (All images are larger when clicked.)

via Flickr

*

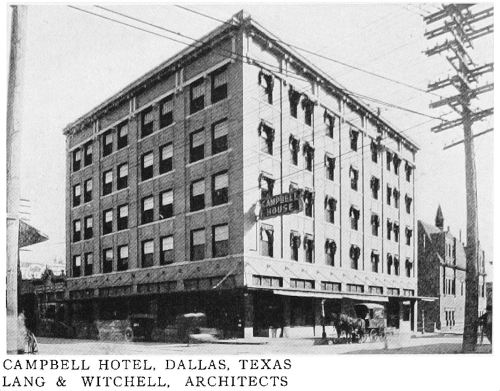

2. THE CAMPBELL HOUSE HOTEL, 2004 Elm Street (southeast corner of Elm & Harwood), designed by Lang & Witchell. A few blocks east on Elm from the Hippodrome was the Campbell Hotel, built in 1910-1911 by Archibald W. Campbell, a man who knew how to invest in Dallas real estate and left an estate worth more than a million dollars when he died in 1917 (a fortune equivalent to almost $20 million today). The Campbell Hotel lasted until 1951, when it was sold and became the New Oxford Hotel. It was demolished sometime before 1970; the site is currently occupied by a parking garage. (See it on a 1921 Sanborn map, here.)

*

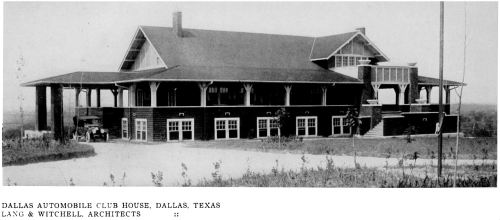

3. DALLAS AUTOMOBILE COUNTRY CLUB, at the time 6 miles north of Dallas (roughly at what is now Walnut Hill and Central Expressway), clubhouse designed by Lang & Witchell. Built in 1913/1914, this club for wealthy “automobilists” was located on what was originally 26 acres donated by W. W. Caruth — in order to get there, you had to drive, which was part of the relaxing experience this golf course-free country club counted as one of its benefits. The club grounds included a 6-acre lake and was a popular site for boating, fishing, and swimming (a top-notch golf course was eventually added). The name of the country club changed a couple of times over the years: it became the Glen Haven Country Club in 1922 and then the Glen Lakes Country Club in 1933. Glen Lakes had a long run, but northward-development of Dallas was inexorable, and the club and golf course were closed in 1977 when the land the country club had occupied for over 60 years was sold for development. (See it on a 1962 map here — straddling Central Expressway — and just try to imagine the value of that land today.)

*

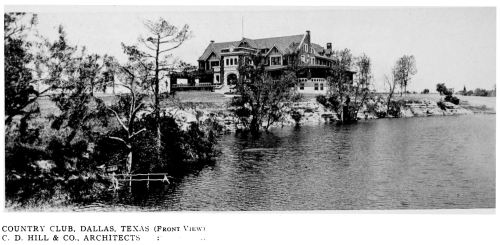

4. DALLAS COUNTRY CLUB, Preston Road & Beverly Drive, clubhouse designed by C. D. Hill. One of the reasons the Dallas Automobile Country Club had to change its name was because people kept confusing it with the granddaddy of Dallas’ country clubs, the Dallas Country Club, in Highland Park, built in 1911 and still the most exclusive of exclusive local clubs and golf courses. (See part of the club’s acreage on a 1921 Sanborn map, here.) (I don’t think any of the original clubhouse still stands, but I could be wrong on this.)

via DeGolyer Library, SMU

via DeGolyer Library, SMU

*

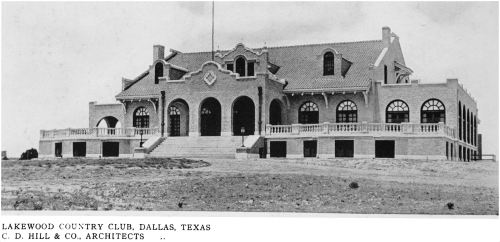

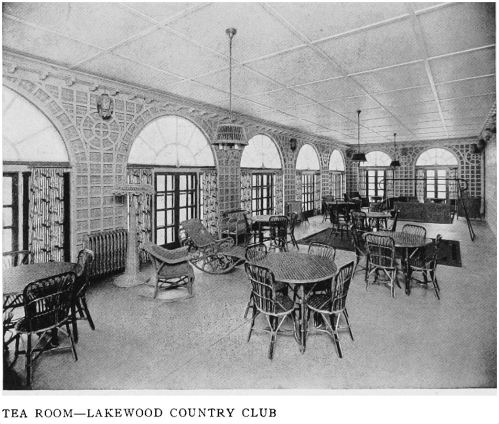

5. LAKEWOOD COUNTRY CLUB, 6430 Gaston Avenue, clubhouse designed by C. D. Hill. This East Dallas country club and golf course was built in 1913-1914 on 110 acres of “rolling prairie and wooded glades, broken with ravines and set with stately trees that offer puzzling hazards” (it was estimated that there were over 1,000 pecan trees on the land). I don’t know anything about golf, but trying to play a round on this original ravine-ravaged course sounds … exhausting. This large structure (which seems too big to be called a “clubhouse”!) stood in Lakewood until it was demolished at the end of 1959 or beginning of 1960 when a new clubhouse was built. (See it on a 1922 Sanborn map — out in the middle of NOTHING — here. Note that many of the street names have changed over the years, including Abrams, which was once called Greenville Rd.)

Dallas Morning News, May 18, 1913

Dallas Morning News, May 18, 1913

*

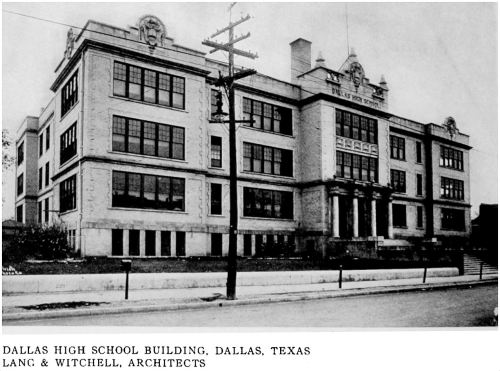

6. DALLAS HIGH SCHOOL, Bryan & Pearl streets, designed by Lang & Witchell. Located on the site of the previous Dallas High School, this new building was built in 1908. For years Dallas’ only (white) high school, the building expanded over the years and has been known by a variety of names (Dallas High School, Bryan Street High School, Crozier Tech, etc.). I like this description of the original “somewhat novel” color scheme of the classrooms: the ceilings were in cream, the “under wall” in warm green, then the blackboards, and beneath them, the walls, in RED. This building has valiantly managed to survive for 110 years — seemingly forever under threat of demolition — but it still stands and, recently renovated into office space, it appears to have a rosy future. (See the main school building on a 1921 Sanborn map here; the gymnasium is here.)

via Flickr

via Flickr

*

7. SEARS, ROEBUCK & COMPANY OF TEXAS, EMPLOYEES’ CLUB HOUSE, S. Lamar & Belleview, designed by Lang & Witchell. I love this little building! When plans for the 1913 expansion of the massive Sears warehouse were drawn up, this modest building was to be a (three-story) clubhouse for employees. A description of the not-yet-built expansion included this:

This clubhouse will contain ample cafeteria, dining room and lunch room [space] to accommodate 600 employees at one time. The main cafeteria will be so arranged that it can be turned into an assembly room for the benefit of the employees, having a stage built at one end, and means will be afforded for all variety of social, musical and athletic activities as may be developed by the employees themselves. (Dallas Morning News, Feb. 5, 1913)

What a perk! But by 1918, Sears had basically outgrown the building (which had ultimately been built as only one story, with a half-basement), and the company offered the use of it to the Dallas YWCA who used it as an “industrial branch” lunchroom/cafeteria (and lounge) in which meals were served to both YWCA members as well as to the general public (including many who worked at Sears). Prices of these wholesome meals served by wholesome girls varied over the years from a nickel to 25 cents — 200-400 patrons were served daily. The building’s half-basement was used as the men’s dining room and as a gymnasium for the YWCA girls (I believe it was also made available to Sears-Roebuck employees). (Read an article about this little “industrial branch” of the YWCA in a Dallas Morning News article from Aug. 15, 1920, here). The YWCA used this Sears building from at least 1918 to 1922. I’m not sure what its use was after the YWCA closed their “Sears-Roebuck Branch,” but I’m delighted to see that it still stands as part of the South Side on Lamar complex. (See the employee club house on a 1921 Sanborn map, here — it appears to be connected to one of the main buildings by a tunnel).

Detail of this postcard

**

Next: churches, firehouses, an art gallery, and a hospital (the last installment!).

***

Sources & Notes

The Western Architect, A National Journal of Architecture and Allied Arts, Published Monthly, July, 1914. This issue, with text and critical analysis in addition to the large number of photographs, has been scanned in it entirety by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign as part of its Brittle Books Program — it can be accessed in a PDF, here (the Dallas issue begins on page 195 of the PDF). Thank you, UIUC!

In this 7- part series:

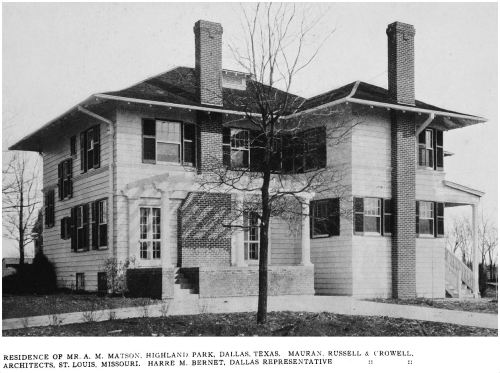

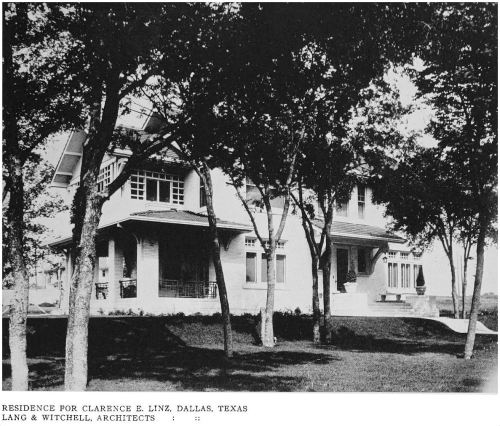

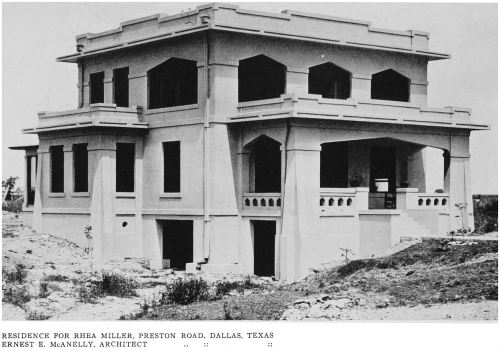

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: Park Cities Residences”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: Residences of East Dallas, South Dallas, and More”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: Skyscrapers and Other Sources of Civic Pride”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: Businesses”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: The Adolphus Hotel”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: Places of Leisure, Etc.”

- “Dallas in ‘The Western Architect,’ 1914: City Buildings and Churches”

*

Copyright © 2018 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.