The Ladies (click for larger image)

The Ladies (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

When one thinks of “ladies’ clubs” of the past, one probably tends to think of groups of largely well-to-do women in fashionable dresses, gloves, and smart hats who gathered for quaint meetings in one another’s homes to discuss vaguely literary or cultural topics, sip tea, chit-chat, and gossip. Often they would plan projects and events which would aid pet community or charitable causes. There were clubs of varying degrees of serious-mindedness, but, for the most part, club meetings were mostly an excuse for women to socialize. 100 years ago, these women rarely worked outside the home, and these groups offered an important social and cultural outlet for well-educated women of means. White women. Women of color were not part of that particular club world. They had to create clubs for themselves. And they did.

In 1892, eight African-American teachers in Dallas organized their own club, the Ladies’ Reading Circle, and while it, too, was an important social outlet for the women, the focus of the group tended to be more serious, with reading lists comprised primarily of political, historical, and critical texts.

The members of the Ladies’ Reading Circle (a group that lasted at least until the 1950s) were, for the most part, middle-class black women who set an agenda for the club of education, self-improvement, and social responsibility. Like most women’s clubs of the time, each meeting of the LRC was held in a different member’s home and usually ended with a “dainty” luncheon and light musical fare, courtesy of the Victrola or player piano; but what set the LRC apart from most of the other women’s clubs of the day was the choice of reading material — from books on world history and international politics, to texts on current affairs and social criticism. (Several surprising examples appear below.)

Not only did the women gather weekly to discuss current and cultural affairs, they also worked to improve their community by tackling important social issues and by inspiring and encouraging young women (and men) who looked to them as civic leaders. Noted black historian J. Mason Brewer dedicated his 1935 book Negro Legislators of Texas to the women of the Ladies’ Reading Circle. The photograph above is from Brewer’s book, as is the following dedication:

Included were the names of the members, several of whom had organized the club in 1892:

One of the LRC’s concerns was establishing a home which, like the white community’s YWCA, offered housing and career training for young women. The charming frame house the club bought for this purpose in 1938 (and which is described in the Jan. 10, 1952 News article “Ladies Reading Circle Seeks $7,500 for Expanding Home”) still stands at 2616 Hibernia in the State-Thomas area

2616 Hibernia (Google Street view, 2014)

2616 Hibernia (Google Street view, 2014)

But the group was organized primarily as a “reading circle,” and the minutes of three randomly chosen meetings show the sort of topics they were interested in exploring. The following three articles are from the post-WWI-era, and all appeared in The Dallas Express, a newspaper for the city’s black community.

April 3, 1920

April 3, 1920

April 10, 1920

April 10, 1920

October 20, 1923

October 20, 1923

My favorite juxtaposition of content on the pages of The Dallas Express was the article below which reported on a white politician’s promise that he would fight to keep “illiterate Negro women” from voting — just a column or two away was one of those eye-popping summaries of the latest meeting of the Ladies’ Reading Circle. My guess is that the black educators who comprised the Ladies’ Reading Circle were probably far more knowledgeable about world events than he was.

May 22, 1920

May 22, 1920

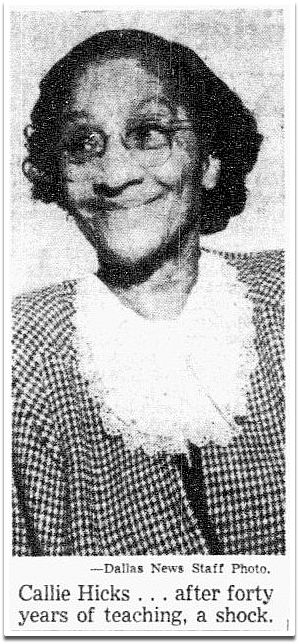

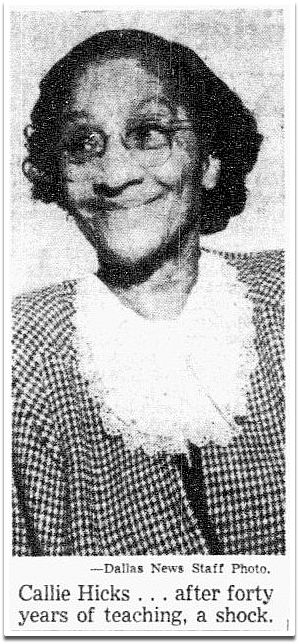

In reading the limited amount of information I could find on the LRC, I repeatedly came across the name of one of the earliest members, Callie Hicks (she is in the 1935 photo at the top, seated, second from the right). She was a dedicated teacher as well as a respected civic leader who worked for several causes and was an executive of the Dallas branch of the NAACP. A Dallas News article about Miss Hicks appeared in Feb., 1950 when she was named “Woman of the Year” by one of the largest African American women’s organizations in Dallas County (“Honor Caps 40 Years of Helpful Teaching,” DMN, Feb. 10, 1950). Miss Hicks died in May, 1965.

1950

1950

It’s a shame that the Ladies’ Reading Circle is not better known in Dallas today. I have to admit that I had never heard of the group until I stumbled across that 1935 club photo. Their tireless work to improve the intellectual lives of themselves and others no doubt influenced the generations that followed.

***

Sources & Notes

Top photograph, dedication, and member list, from Negro Legislators of Texas and Their Descendants; A History of the Negro in Texas Politics from Reconstruction to Disenfranchisement by J. Mason Brewer (Dallas: Mathis Publishing Co., 1935).

Minutes from the Ladies’ Reading Circle meetings all printed in The Dallas Express.

Relevant material on the LRC and other historic African-American women’s clubs can be read in Women and the Creation of Urban Life, Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920 by Elizabeth York Enstam (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1998), here.

The Handbook of Texas entry for one of the founding members of the Ladies’ Reading Circle, Julia Caldwell Frazier, can be found here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved

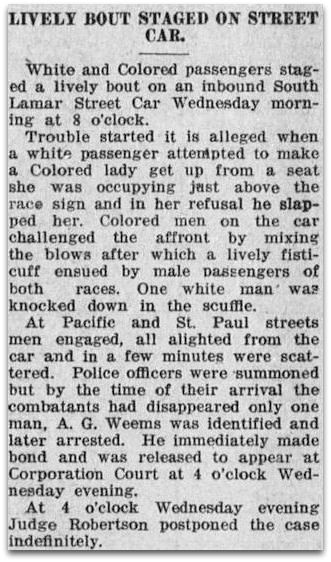

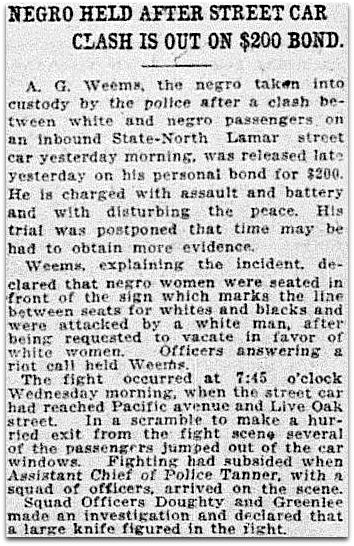

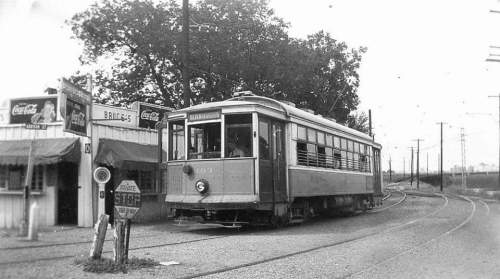

The Dallas Express, Oct. 4, 1919

The Dallas Express, Oct. 4, 1919 Dallas Morning News, Sept. 25, 1919

Dallas Morning News, Sept. 25, 1919 Dallas Express, July 12, 1919 (click for larger image)

Dallas Express, July 12, 1919 (click for larger image)

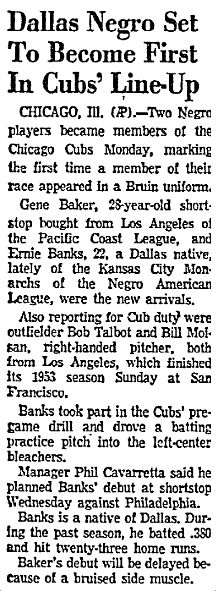

AP, Sept. 15, 1953

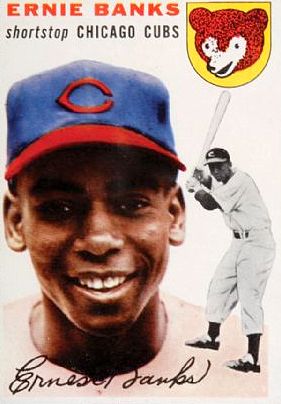

AP, Sept. 15, 1953 Ernie Banks’ rookie card – Topps, 1954

Ernie Banks’ rookie card – Topps, 1954

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art)

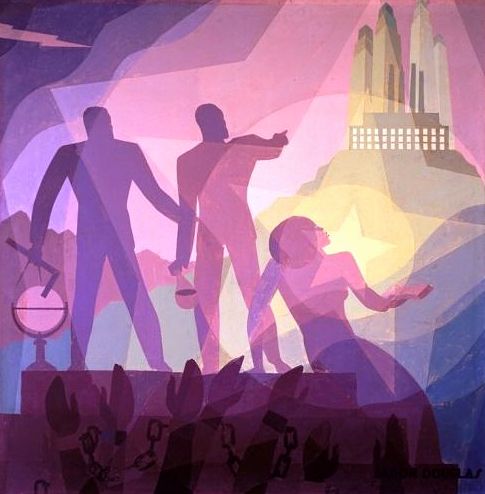

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art) “Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco)

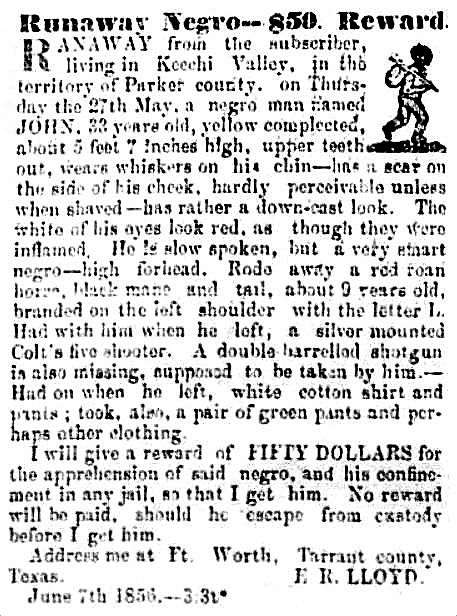

“Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco) Dallas Herald, June 7, 1856

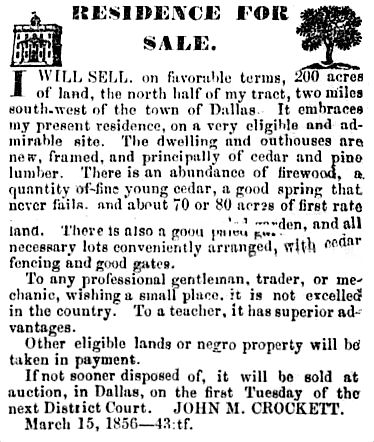

Dallas Herald, June 7, 1856 March 15, 1856

March 15, 1856 Sept. 15, 1858

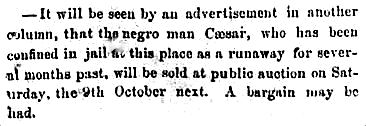

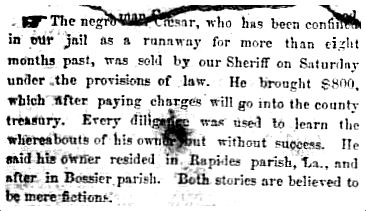

Sept. 15, 1858 Oct. 20, 1858

Oct. 20, 1858 1861

1861

April 3, 1920

April 3, 1920 April 10, 1920

April 10, 1920 October 20, 1923

October 20, 1923 May 22, 1920

May 22, 1920 1950

1950