Jim Conner, Not-So-Mild-Mannered RFD Mail Carrier

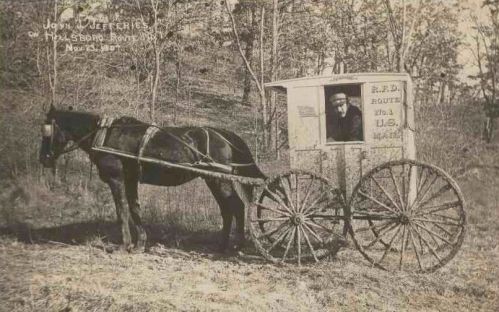

An RFD mail carrier… (click for larger image)

An RFD mail carrier… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

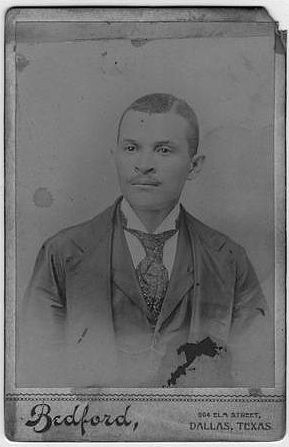

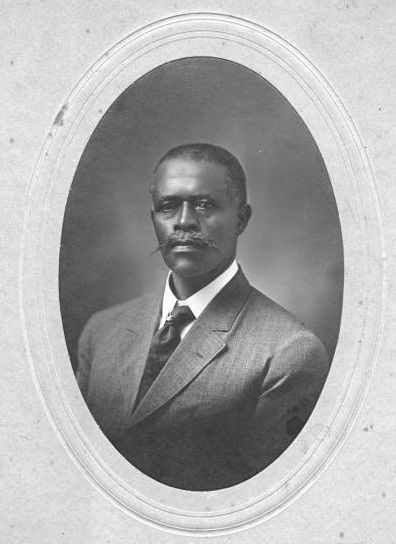

The man in the photo below looks like every character actor working in Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s.

But he wasn’t an actor — he was a retired Dallas postal worker who began his career in 1901 as a rural mail carrier when the Rural Free Delivery (RFD) system was implemented in Dallas. (Before this, those who lived beyond the city limits — generally farmers — had to trek to a sometimes distant outpost — such as a general store — to pick up their mail.) RFD service began locally on October 1, 1901, and an 18-year old Jim Conner was one of six men hired to work the new mail routes beyond the city.

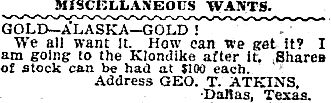

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901

When Rural Free Delivery service began in Dallas, four rural post offices were closed: Lisbon, Wheatland, Five Mile, and Rawlins (the office at Bachman’s Branch, which Jim Conner’s route replaced).

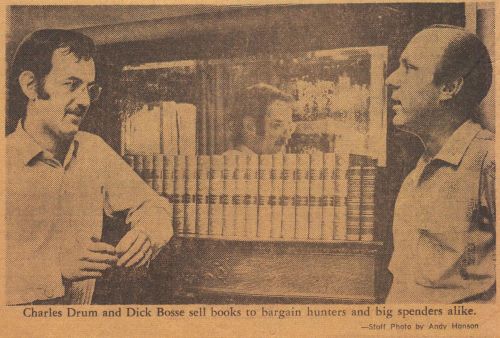

In a 1940 interview with The Dallas Morning News, Conner talked about his early postal route (Route 5), which was 32 miles long; before the arrival of automobiles, he traveled on horseback, by horse cart, by buggy and cart, or by bicycle. The photo at the top shows what early RFD mail wagons looked like.

Jim’s route took him well beyond the city limits: out Cedar Springs to Cochran’s Chapel, to within a mile of Farmers Branch, and over to Webb’s Chapel by way of the “famous” Midway Church and School corner (which became Glad Acres Farm); he returned on Lemmon Avenue. It took him 8 hours if the weather was nice; if the weather was particularly bad, it could take 12 to 15 hours to complete his appointed rounds. He was paid $500 a year and was required to keep two horses, a cart, a buggy, and saddles. He retired in 1935.

**

So. A delightfully nostalgic walk down memory lane with an avuncular-looking guy we all kind of feel we know. I thought I’d do a quick search to see if there was an obituary for Jim — there was: he died in 1956 at the age of 73, survived by his wife, 11 children (!), 22 grandchildren, and 3 great-grandchildren. But in addition to the obit, I found something else: a report of a shooting, an arrest, and a charge with “assault to murder.”

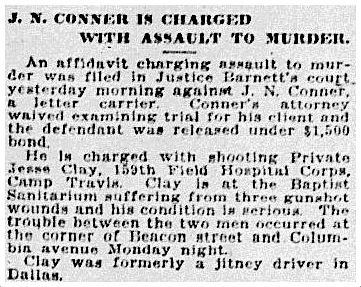

DMN, Jan. 2, 1918

DMN, Jan. 2, 1918

What?!!

Though the account of the incident is described as being “somewhat vague,” on New Year’s Eve, 1918, Jim Conner shot a soldier named Jesse Clay after “words” were exchanged at the corner of Beacon and Columbia in Old East Dallas. There had been bad blood between the two in the past, and the New Year’s Eve situation apparently escalated quickly. Clay had been walking down the street with a lady-friend when Conner’s car came to a stop next to them. Clay (described as being drunk at the time) forced his way into the car, and Conner, fearful of being attacked, reached for a gun in the back seat. The two tussled and, after they were both out of the car, Conner saw that Clay also had a gun. This was when Conner shot him three times, intending, he said, to merely wound him. Clay shot back but missed. (The entire account, as it appeared in The Dallas Morning News on Jan. 1, 1918 can be read in a PDF here.)

The soldier was badly injured, with two of the three shots hitting his chest. He was not expected to live. Conner had surrendered to police at the scene and was charged with “assault to murder.” The last report on this incident that I could find was on Jan. 3, in which Clay was described as being in “very critical condition.”

So what happened? As Conner spent a full career as a postal employee, it seems unlikely he was tried for murder. I used every possible combination of search words I could think of but found nothing more on this case. The story just disappeared. I did find a 1943 obituary for a Jesse P. Clay (killed while working on an Army Air Force Instructors School runway when he was struck by the wing of an airplane coming in for a landing), and it seems likely that it was the same guy — he was about the right age, he was a career military man, he lived in Dallas most of his life, and he was born in Kentucky. I assume the soldier in question (who would have been 37 at the time of the shooting) survived his gunshot wounds and that charges against Conner were either dismissed (with Conner pleading self-defense?) or settled (perhaps the military intervened to keep the story out of the press — this was during the height of WWI). Whatever actually happened, it seems that both men were able to move on from that really, really bad New Year’s Eve, a night I’m sure neither forgot.

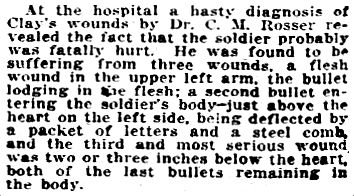

My favorite little detail in the story of this sordid shooting was the line in the initial newspaper report in which it was revealed that one of the (potentially deadly) bullets was “deflected by a packet of letters and a steel comb.” How appropriate that the thing that probably saved mailman Jim Conner from a murder rap was “a packet of letters.” (…And a steel comb, but that doesn’t fit in with my narrative quite so well. Although Mr. Conner does look quite well-groomed.)

DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

***

Sources & Notes

Real-photo postcard of Hillsboro, Wisconsin RFD mail wagon is from eBay.

The full DMN account of the bizarre 1918 shooting can be read in a PDF, here.

An informative site on history of Rural Free Delivery — with lots of photos — can be found here.

“RFD”? Wiki’s on it, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

1890

1890

ca. 1910-15

ca. 1910-15 Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894

Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894 The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

DMN, June 15, 1922

DMN, June 15, 1922 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jan. 28, 1964

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jan. 28, 1964 Corpus Christi Caller-Times, April 29, 1948

Corpus Christi Caller-Times, April 29, 1948

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

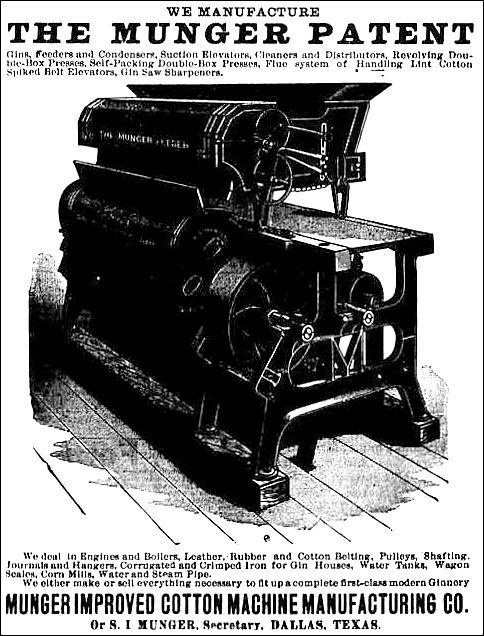

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888 DMN, June 3, 1888

DMN, June 3, 1888  DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897 DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918 DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920