Zap Those Extra Pounds Away in Mrs. Rodgers’ Electric Chair — 1921

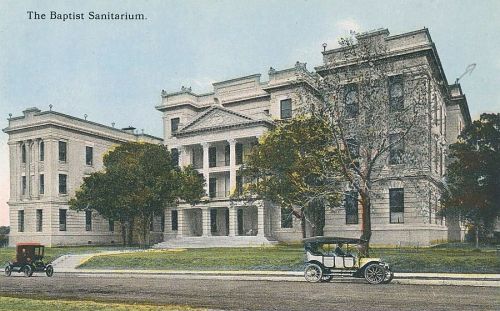

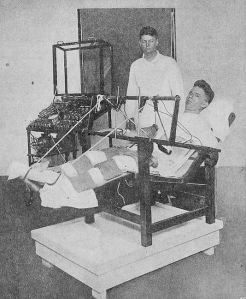

Throwing the switch in 3-2-1… (click for larger image)

Throwing the switch in 3-2-1… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

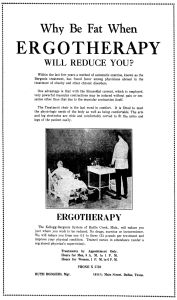

While looking for something completely unrelated (which is always the best way to find unexpected things), I came across this full-page ad which appeared in the Sept. 9, 1921 edition of The Jewish Monitor (click to see a larger image):

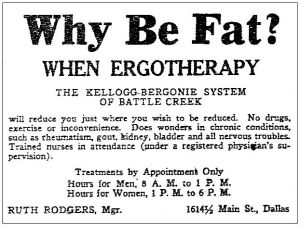

Why Be Fat When

E R G O T H E R A P Y

WILL REDUCE YOU?

Within the last few years a method of automatic exercise, known as the Bergonie treatment, has found favor among physicians abroad in the treatment of obesity and other chronic disorders.

One advantage is that with the Sinusoidal current, which is employed, very powerful muscular contractions may be induced without pain or sensation other than that due to the muscular contraction itself.

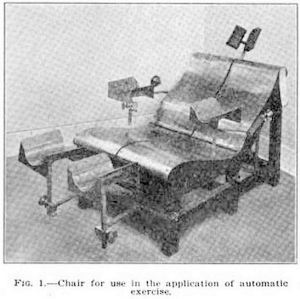

The Treatment chair is the last word in comfort. It is fitted to meet the physiologic needs of the body as well as being comfortable. The arm and leg electrodes are wide and comfortably curved to fit the arms and legs of the patient easily.

ERGOTHERAPY

The Kellogg-Bergonie System of Battle Creek, Mich., will reduce you just where you wish to be reduced. No drugs, exercise or inconvenience. We will reduce you from one (1) to three (3) pounds per treatment and improve your physical condition. Trained nurses in attendance (under a registered physician’s supervision).

Treatments by Appointment Only

Hours for Men, 8 A.M. to 1 P.M.

Hours for Women, 1 P.M. to 6 P.M.

Phone X 5759

Ruth Rodgers, Mgr.

1614 1/2 Main Street, Dallas, Texas.

*

“The arm and leg electrodes are wide and comfortably curved” — there’s a line one doesn’t often encounter in an ad!

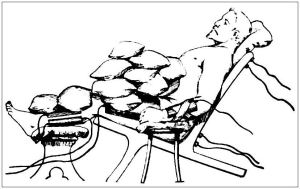

So what was this treatment of obesity that required “no drugs, exercise or inconvenience”? Well, basically, it was a low-voltage electric chair in which the naked, smock-draped “patient” reclined on wet towels and was covered with sandbags (which weighed up to 100 pounds). Electrodes were attached to the arms, legs, and abdomen. When the switch was flipped, electrically-provoked exercise began, and electric current caused muscular contractions (up to 100 a minute) without fatigue to the “exerciser.” All sorts of physiologic things were happening during these sessions, including a whole bunch of sweating. Patients would lose from 1 to 3 pounds during their time in the chair, hose themselves down and walk away refreshed.

Jean Albard Bergonié (1857-1925) was a French doctor/researcher/inventor who specialized in radiology in the treatment of cancer, and this odd electric chair was something of a departure from his oncology studies. It was used to treat a variety of ailments and conditions such as obesity, heart conditions, diabetes, “suppressed uric acid elimination,” and, later shell-shock. Professor Bergonié died in 1925 as the result of prolonged exposure to radium in his research to find a cure for cancer (in the years before his death, he had lost an arm and fingers to continual X-ray exposure). The Institut Bergonié continues in Bordeaux, France as a cancer research center.

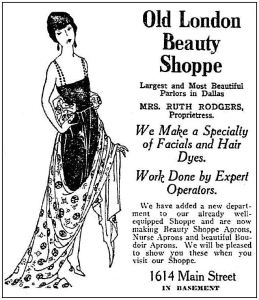

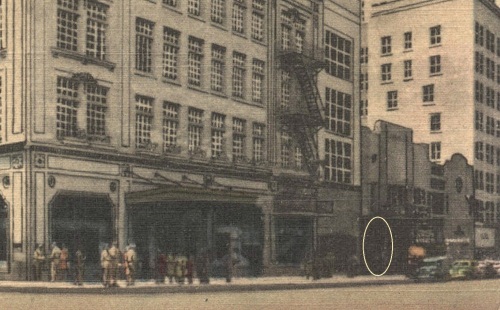

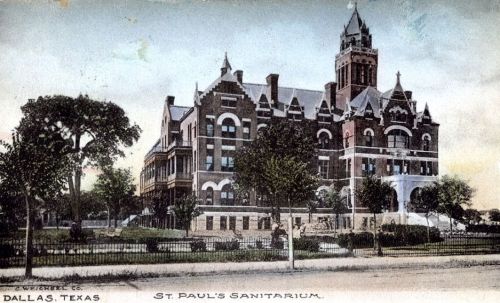

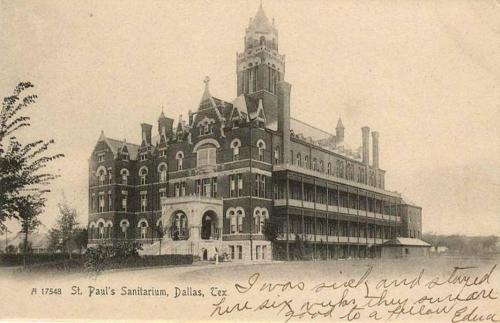

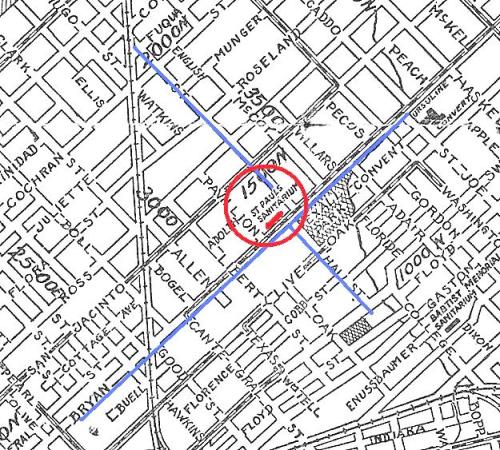

So back to the chair. By the time of the 1921 ad above, Bergonié’s “ergotherapy” had become a weight-loss feature in beauty spas and salons. The ads I found mentioning the electric chair as something corpulent men and women of means might have seen in Dallas newspapers appeared between July and October of 1921, touting the miracle chair at Mrs. Ruth Rodgers’ beauty salon, The Old London Beauty Shoppe at 1614 ½ Main Street, a couple of doors from Neiman-Marcus.

I don’t know if it didn’t catch on or whether it just wasn’t mentioned in ads, but the chair made its final appearance in an Old London Beauty Shoppe ad in early October of the same year.

The splashiest news about Bergonié’s invention was a few months later, in early 1922, when it was revealed that the UK’s Queen Mary had availed herself of the chair in order to slim down in time for her daughter’s wedding, with Prof. Bergonié himself apparently operating the current flow. The best part of the lengthy and breathless article about the plump royal allowing herself to lie in this electric chair as she was rather unceremoniously weighted down with royal sandbags was this sentence:

[Mrs. David Lloyd George, the wife of the British prime minister] lost no time in telling Queen Mary all she knew about Professor Bergonie, the famous French ergotherapist, and his marvelous electric chair, which is said to jar fat from the human frame with the ease and almost the rapidity of a man peeling a tangerine.

Hey, I want that!

One would assume that sort of free publicity would be a boon to spas and salons offering State-side ergotherapy — I have a feeling Mrs. Rodgers had moved on by then and was probably kicking herself for concentrating on the more mundane treatment of wrinkles and sagging skin and the administering of marcel waves (her specialty).

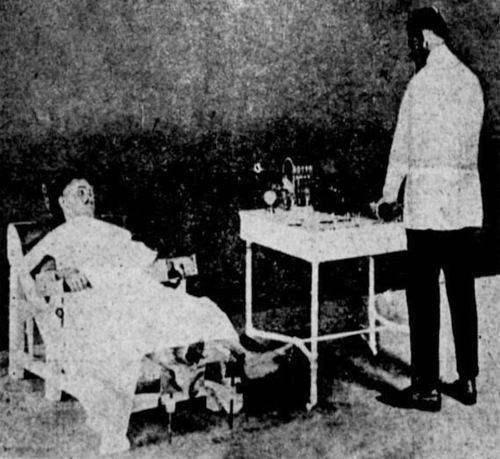

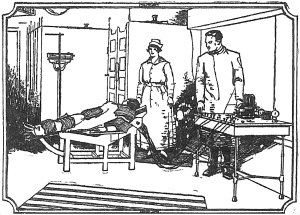

Below, some views of The Chair over the years (all pictures larger when clicked).

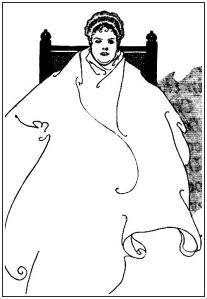

Above, a drawing from a 1913 medical book, found here.

*

From the journal Medical Record, May 1, 1915.

*

A World War I soldier being treated for shell-shock, from The Electrical Experimenter (Feb. 1919), here (continued here).

*

Ruth Rodgers was the proprietress of the Old London Beauty Shoppe (later the Old London School of Beauty Culture), which seems to have operated in Dallas from the ‘teens to at least the late-1930s. The location during the period of the ergotherapeutic chair was in the basement of 1614 Main Street.

*

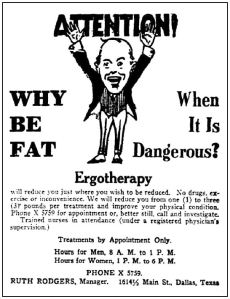

Mrs. Rodgers did it all. That might be her in the ad.

*

*

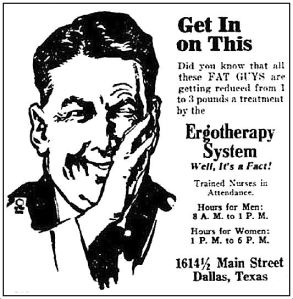

It’s a bit unusual seeing ads like this directed toward men.

*

San Francisco Chronicle, Sept. 25, 1925

*

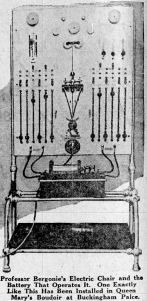

Above, a very Aubrey Beardsley-esque depiction of the “distressingly stout” Queen Mary, ready to undergo her course of treatments. Read the full, widely-circulated article from February, 1922, “Queen Mary’s Jarring Anti-Fat Ordeal; Yearning for a Girlish Figure to Grace Her Daughter’s Wedding, the Queen-Mother Got One by Sitting in an Electric Chair and Losing 3½ Pounds a Week,” here. (They don’t write headlines like that anymore….) The photo below, showing the control panel, was also part of the article.

*

The caption for this photo (which appeared five years after the cutting-edge Ruth Rodgers was offering it to Dallas patrons): “The new French electric chair on which one reclines in comfort while form-fitting electroids [sic] direct the fat-melting current, as demonstrated by Alice Harris, a stage beauty who must keep thin.” (Ogden Standard-Examiner, April 18, 1926)

*

And, finally, to bring this back to Dallas, the location of Mrs. Rodgers’ Old London Beauty Shoppe in 1921 — 1614½ Main Street (basement) — is circled (this building was later the Everts Jewelry store before it moved across the street to the north side of Main). To the left is Neiman-Marcus, at the corner of Main and Ervay. (Full view of this postcard, from the collection of the DeGolyer Library, SMU, is here.)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo is a detail from the ad below, which appeared in the Sept. 9, 1921 edition of The Jewish Monitor; it can be accessed via the Portal to Texas History, here.

Read a doctor’s account of just how Bergonie’s chair worked, in the article “Modern Treatment of Obesity” by Edward C. Titus (Medical Record, Jan. 24, 1920), here.

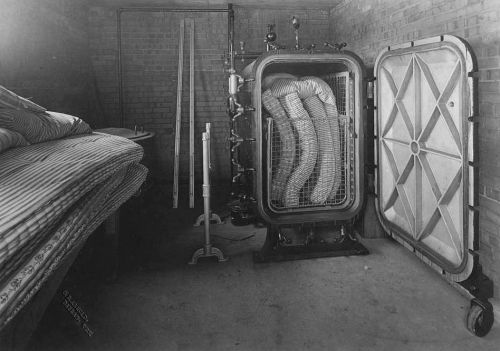

I’m not sure about the connection of this chair to J. H. Kellogg (the treatment in the ad was referred to as “The Kellogg-Bergonie System of Battle Creek, Mich.”). It appears that he and Bergonie might have developed similar chairs independently of one another and decided to form some sort of partnership — either by mutual agreement or court edict. Here is a photo of Kellogg’s “patented electrotherapy exercise bed” used in his Battle Creek sanitarium:

via Oobject (more Kellogg contraptions here)

And speaking of Mr. Kellogg, might I direct your attention to a previous Flashback Dallas post — “Electricity in Every Form — 1909” — here.

Click pictures for larger images

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Mary Roberts Wilson (1914-2001)

Mary Roberts Wilson (1914-2001)

The exclamation mark is a nice touch — 1878

The exclamation mark is a nice touch — 1878 Dallas Herald, Dec. 30, 1877

Dallas Herald, Dec. 30, 1877 Galveston Daily News, July 28, 1889

Galveston Daily News, July 28, 1889 Dallas Morning News, July 28, 1889

Dallas Morning News, July 28, 1889

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951 Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951 Volk ad — 1951

Volk ad — 1951 W. A. Green ad — 1951

W. A. Green ad — 1951