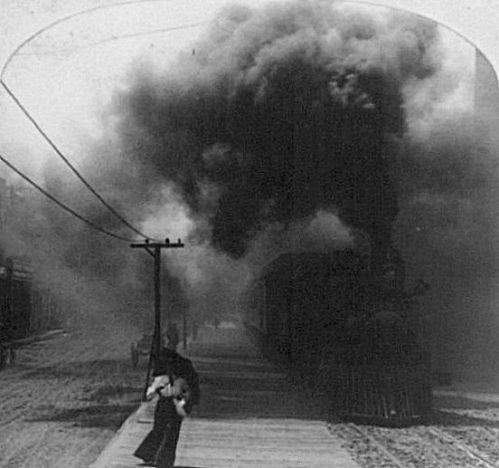

Dallas Rapid Transit, Est. 1888

Ride the Cyclone to Fair Park… (click for larger image)

Ride the Cyclone to Fair Park… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

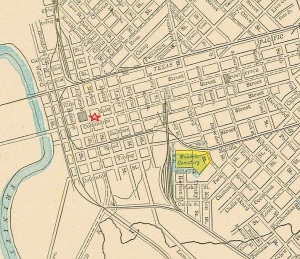

The Dallas Rapid Transit Railway chugged into town in 1888, going from charter to operation in seven months. And that included laying their own track. The “dummy” steam engine (a locomotive designed to appear more like a friendly little streetcar and less like a hulking locomotive) seen above, carried passengers from the Windsor Hotel at Commerce and Austin through South Dallas (via S. Lamar and Forest Ave., now MLK Blvd.) to Fair Park. It started business just in time to ferry crowds to the State Fair. The fare was 20 cents, which seems pricey, but this might have been “surge” pricing charged only during the “Greatest Fair and Exposition in the World.” (According to the Inflation Calculator, 20¢ in 1888 would be the equivalent to more than $5 in today’s money.)

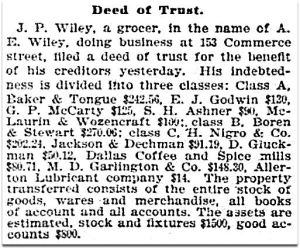

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 14, 1888

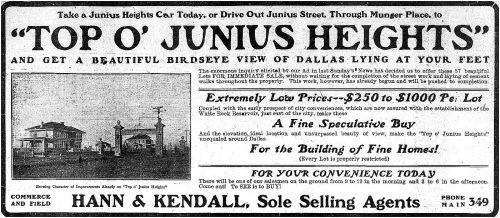

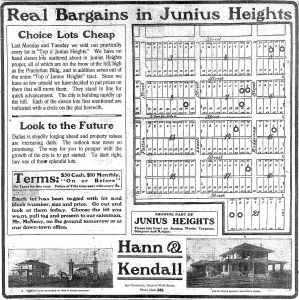

The new street railway was particularly appreciated by developers looking to sell land in southern Dallas, still considered a “suburb” in the 1880s. Residential streetcar service was essential to prospective builders and buyers, and as soon as the Rapid Transit line was up and running, its name was popping up in South Dallas real estate ads for additions with names like Chestnut Hill, Edgewood, and South Park.

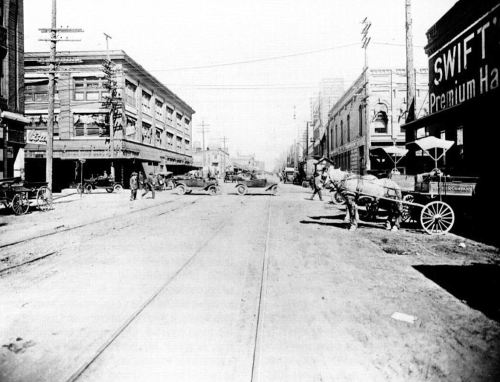

In March of 1890 — after a year and a half of steady growth — the Dallas Rapid Transit Railway went electric, tossing out their old steam-powered cars (not even 18 months old!) for brand new, ultra-modern cars powered by electricity. (For a bit of perspective, parts of the country were still relying on the really old-fashioned mule-drawn streetcars.) Dallas’ first electric-powered streetcar hit the rails on March 9, 1890.

Understandably, the sight of these newfangled streetcars was quite the topic of fascinated conversation. How exactly did they work, anyway? The Dallas Morning News published an article with helpful information for the Dallasites of 1890 (and 2016!). (Click to see larger image.)

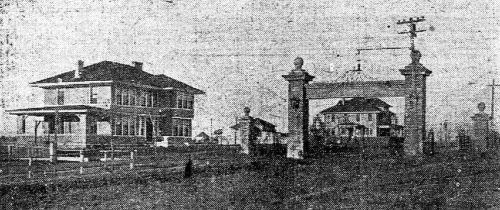

The photo below (which appears in the great book McKinney Avenue Trolleys) is a staged publicity photo with a woman at the helm, showing that the new electric streetcar was so easy to operate that “even a woman” could do it. In tow behind the sparkling new electric streetcar was the old, past-it steam car, with its engineer racing to try to catch up with the new technology. Get with it, man, it’s 1890!

Southern Traction, April 10, 1973 (via McKinney Avenue Trolleys)

Southern Traction, April 10, 1973 (via McKinney Avenue Trolleys)

Dallas Public Library photo (via McKinney Avenue Trolleys)

Dallas Public Library photo (via McKinney Avenue Trolleys)

Initially, the track was only 4 miles long, but that had more than doubled soon after the switch to electric cars.

Things seemed to be going well. The company was expanding, speeds were increasing, and … “No dust” !

But … in 1894 the company went into receivership and was sold in December of that year for $35,000.

It appears that the company struggled on under different owners and slightly different names through at least 1909, but instead of those twilight years being filled with reflective contemplation and bass fishing, they were spent mired in endless lawsuits.

But let’s not dwell on the sputtering end of a business — let’s look back to the beginning, when the H. K. Porter Co. of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania was proud to show off its new light locomotive with the noiseless steam motor which was headed, full of hope and enthusiasm, for the little city that could, Dallas, Texas.

**

The steam-powered Cyclone — seen at the top — went on an adventure through the streets of downtown in 1889 when, under a full head of steam, it jumped the tracks and kept on going down paved streets until it crashed into a curb on Main!

***

Sources & Notes

Image at the top (and bottom), “Dallas Rapid Transit, ‘Cyclone’ Locomotive No. 1,” from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University; more information here.

Read an interview with J. E. Henderson, president of the Dallas Transit Railway company, commenting on his new street railway (“The New Rapid Transit,” DMN, Oct. 14, 1884) here (yes, it IS difficult to read!).

The two photos of Dallas Rapid Transit electric streetcars are from the book McKinney Avenue Trolleys by Jim Cumbie, Judy Smith Hearst, and Phillip E. Cobb (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2011). If you’re interested in this topic, this book seems pretty essential!

The history of early streetcars in Dallas can be read in the pages of the WPA Dallas Guide and History here (scroll to the bottom of the page and continue to the following page).

Photos and clippings are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

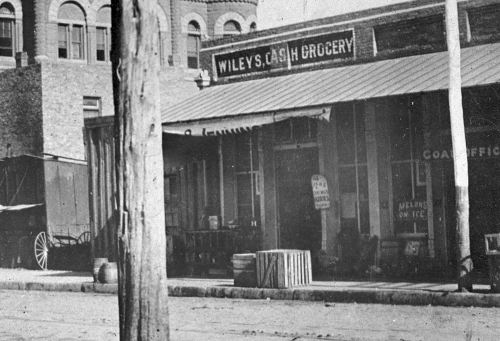

Andrew Bateman Couch, pharmacist

Andrew Bateman Couch, pharmacist