The Highland Park pagoda… (click for larger image)

The Highland Park pagoda… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

I never heard of the Gill Well growing up — in fact, it wasn’t until around the time I started this blog — about three or four years ago — that I first became aware of it. Though largely forgotten today, the Gill Well used to be a pretty big deal in Dallas: for years, early-20th-century entrepreneurs tried valiantly and persistently to capitalize on the mineral-heavy artesian water from this well — the plan was to use this hot spring water in order to turn Dallas (or at least Oak Lawn) into, well, “the Hot Springs of Texas.” We came so close!

So — Gill Well? Who, what, when, where, why, and how?

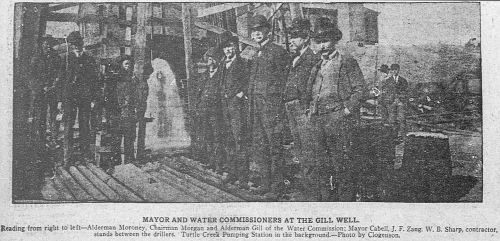

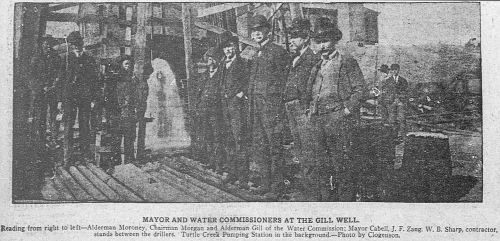

In 1902 city alderman and water commissioner C. A. Gill proposed sinking an artesian well near the Turtle Creek pumping station in order to determine if the flow of water in underground springs was sufficient to augment Dallas’ water supply (there was, at the time, another such test well being drilled in West Dallas). The City Council was on board and wanted this test well to be a deep well, “the deepest in the state — in order to settle once and for all the question as to whether or not there lies beneath the earth in this section a body of water, or ‘an underground sea,’ as some call it, of sufficient size to supply the needs of all the people” (Dallas Morning News, Aug. 6, 1902).

Fellow alderman Charles Morgan explained Gill’s proposition to the people of Dallas in a prepared statement to the Morning News:

By sinking artesian wells it is not intended to abandon the plans proposed to secure an adequate storage supply from surface drainage, but that the artesian wells shall augment the supply. We can not get too much water, but if we secure an ample artesian supply our storage basins will be reserve. There will be no conflict. We simply make success double sure. (Alderman Charles Morgan, DMN, Aug. 24, 1902)

The well was sunk in September or October of 1902 near the Turtle Creek pumphouse (which was adjacent to where a later station was built in 1913, the station which has been renovated and is now known as the Sammons Center for the Arts — more on the construction of that 1913 station and a photo of the older pumphouse can be found here); the drilling was slow-going and went on until at least 1904, reaching a depth of more than 2,500 feet. It’s a bit out of my area of expertise, but, basically, good, palatable artesian water from the Paluxy sands — water “free from mineral taint” — was found, but, deeper, a larger reservoir of highly mineralized “Gill water” — from the Glen Rose stratum — was found. That was good news and bad news.

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 1, 1903

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 1, 1903

The “bad news” came from the fact that a part of a pipe casing became lodged in the well, causing an obstruction in the flow of the “good” water from the Paluxy formation. Again, it’s a bit confusing, but the heavy flow of 99-degree-fahrenheit mineral water (which was corrosive to pipes) threatened to contaminate the “good” Paluxy water … as well as the water from the Woodbine formation from which most (all?) of the private wells in Dallas secured their water. (Read detailed geological reports on the well in a PDF containing contemporaneous newspaper reports here — particular notice should be paid to the comprehensive overview of the well and its problems which was prepared for the Dallas Water Commission by Engineer Jay E. Bacon and published in the city’s newspapers on May 10, 1905).

So what the City of Dallas ended up with as a result of this Gill Well was a highly dependable source of hot mineral water. But what to do with it? Monetize it!

As part of the city’s water supply, the mineral water was made available to Dallas citizens free of charge: just show up at one of the handful of pagoda-covered dispensing stations with a jar, a bucket, or a flask, and fill up with as much of the rather unpleasant-smelling (and apparently quite powerful!) purgative as you could cart home with you. (For those who didn’t want to mingle with the hoi polloi, home delivery was available for a small fee.) One such “pagoda” was erected a short distance away, in front of the city hospital (Old Parkland) at Maple and Oak Lawn (the healthful water was also piped directly into the hospital for patient use).

Brenham Weekly Banner, April 6, 1905

One man, however, began offering the water for sale beyond Dallas, hoping to cash in on the free-flowing tonic (see the mineral-content breakdown here), but the city clamped down on him pretty quickly as he was not an authorized agent. From his 1906 ad, one can see that the reputation of Gill water and its healing and restorative powers was already widely known.

DMN, Aug. 2, 1906

If the water was not to be sold, what was the City of Dallas going to do with it? It was decided to pipe the the water a short distance from the test well to nearby property adjacent to the land now occupied by Reverchon Park, then lease the access to the water to a capitalist who would build a sanitarium/spa where people could come to “take the waters” — to bathe in the naturally warm, mineral-heavy artesian water with mystical recuperative properties. The sanitarium would make money by charging its patrons for its services, and the city would collect a small annual income based on the number of the sanitarium’s bathing tubs and the amount of water used:

Compensation to the city shall be $10 per tub per year and one-half-cent per gallon for all water used. (DMN, Jan. 4, 1907)

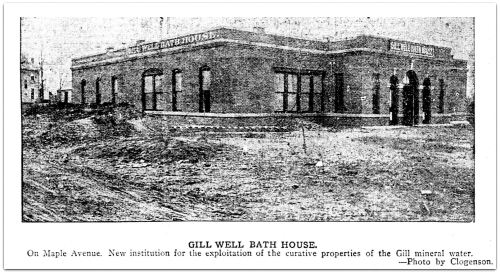

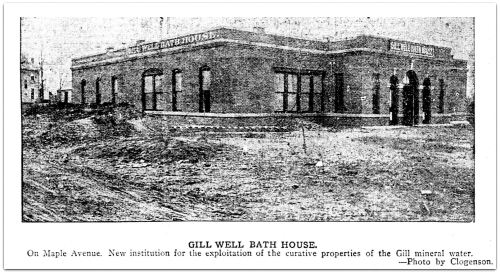

The Gill Well Sanitarium and bath house opened in January 1907, on Maple Avenue just north of the MKT Railroad (now the Katy Trail). (Most clippings and pictures in this post are larger when clicked.)

DMN, Jan. 4, 1907

DMN, Jan. 4, 1907

I searched and searched and searched for a picture of the building and, hallelujah, I finally found one, in the pages of The Dallas Morning News, taken by photographer Henry Clogenson. (This is the only picture I’ve been able to find of it, and, I have to say, it’s not at all what I expected the building to look like. It actually looks like something you’d see in a present-day strip mall.)

DMN, Jan. 13, 1907

DMN, Jan. 13, 1907

Advertisement, DMN, Jan. 6, 1907

Business at the new sanitarium was very good, and the public fountains/spigots at both the sanitarium property and a block or so away at the city hospital continued to be popular with residents who needed a boost or a “cure” and stopped by regularly for a sip or a pail of the free mineral water.

1910 ad

1910 ad

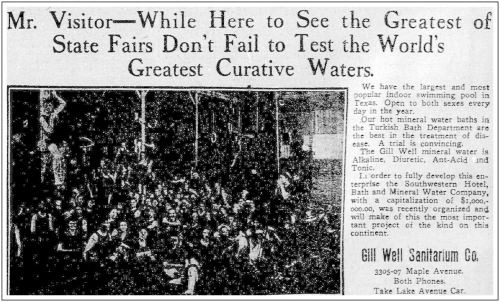

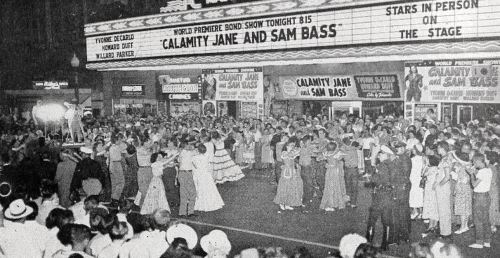

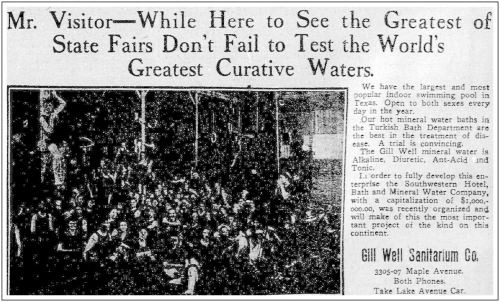

In 1912 a natatorium (an indoor swimming pool) was added and proved even more popular. It was open to men, women, and children; admittance and bathing suit rental was 25¢ (about $6.50 in today’s money). (Contrary to the headline of the ad below, it was not Dallas’ first natatorium — there was one near City Park on South Ervay by at least 1890 — but it was probably the first pool in the city filled with warm mineral water.)

DMN, April 14, 1912

DMN, July 7, 1912

Courtesy of the Texas Swimming and Diving Hall of Fame

Courtesy of the Texas Swimming and Diving Hall of Fame

DMN, Oct. 6, 1912

DMN, Oct. 6, 1912

The last paragraph of the ad above mentions a plan to pipe Gill water to a hotel downtown — not only would the Gill Well Sanitarium Company’s services be offered in the heart of the city amidst lavish hotel surroundings (instead of in Oak Lawn, way on the edge of town), but the company would also be able to compete with Dallas’ other (non mineral-water) Turkish baths — then they’d really be rolling in the cash. As far as I can tell, nothing came of the plan, but the men behind it were pretty gung ho, as can be seen in this rather aggressive advertorial from the same year:

The Standard Blue Book of Texas, 1912

The Standard Blue Book of Texas, 1912

All seemed to be going well with the sanitarium until the city and the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad (the MKT, or the Katy) decided to remove the railroad’s grade crossings through the Oak Lawn area (all work which was to be paid for by the railroad). Double tracks were to be added and crossings were either raised or the streets were lowered. The crossings affected were Lemmon, Cedar Springs and Fairmount (where street levels were cut down to go under the tracks) and Hall, Blackburn, and Bowen (where tracks would be elevated). Also affected: Maple Avenue. (Read more about the MKT plan in the Dallas Morning News article from Aug. 23, 1918 — “Dallas Is Eliminating Four Grade Crossings” — here.)

The Maple Avenue-Katy Railroad crossing had long been a dangerous area for wagons, buggies, and, later, automobiles. Not only was it at the top of a very steep hill (see what that general area north of that crossing looked like around 1900 here), but it also had two sharp curves. The decision was made to straighten Maple Avenue between the approach to the railroad crossing and Oak Lawn Avenue at the same time Maple was being lowered and the Katy track was being raised. (Read the announcement of this plan — “Straighten Maple Avenue Is Plan” — from the Nov. 29, 1917 edition of The Dallas Morning News, here.) The only problem — as far as the Gill Well Sanitarium was concerned — was that the straightened road would go directly through the sanitarium property. I don’t know if the long-time owner of the sanitarium, J. G. Mills, knew about this approaching dire situation, but in 1915 — just a few short months after boasting in advertisements that more than 50,000 patients had availed themselves of the sanitarium’s amenities in 1914 — he placed an ad seeking a buyer of the business (although, to be fair, he’d been trying to sell the company for years):

DMN, Aug. 8, 1915

DMN, Aug. 8, 1915

(In the ad he states that the buyer had an option to purchase the actual well, but the city had never expressed any desire to sell either the well or the full rights to the water.)

The Gill Well Sanitarium Co. appears to have been dissolved in 1916, but there was still hope that a sanitarium/hot springs resort could continue on the property. In 1917, interested parties petitioned the city to change its plans to straighten Maple, arguing that it would destroy any ability to do business on the site, but the city went forward with its plans, and in November 1919, the City of Dallas purchased the land from the group of partners for $21,500 (about $305,000 in today’s money).

DMN, Nov. 13, 1919

The monetization of water from Dallas’ fabled Gill Well ended after ten years.

I had never heard of Maple Avenue being straightened. Below is a map of Turtle Creek Park (which became Reverchon Park in 1915), showing Maple’s route, pre-straightening — the main buildings of the sanitarium were in the bulge just west of Maple, between the Katy tracks and the boundary of the park.

1915 map, via Portal to Texas History

Another view can be seen in a detail from a (fantastic) 1905 map, with the approximate location of the Gill Well Sanitarium circled in white:

Worley’s Map of Greater Dallas, 1905

Worley’s Map of Greater Dallas, 1905

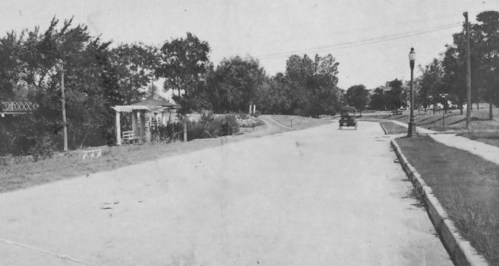

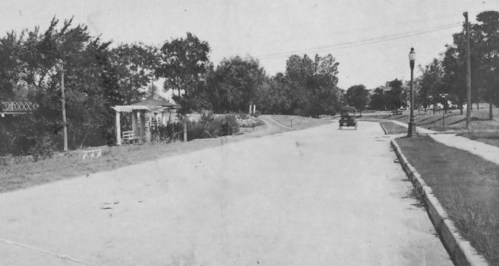

A year or more ago I saw the photo below on the Big D History Facebook page but had no idea at the time what I was looking at: it apparently shows Maple Avenue in 1918, taken from about Wolf Street (probably more like Kittrell Street), which was then near the city limits, looking north. You can see the curve Maple makes and the steep hill — that large building at the right must be the sanitarium and/or the later-built natatorium.

The photo below shows the road-straightening in progress, with the MKT bridge now spanning Maple Avenue.

Dallas Public Library

Dallas Public Library

And here it is almost a hundred years later:

Google Street View, 2014

Google Street View, 2014

So the Gill Well Sanitarium and Bath House was closed, the land was purchased by the City of Dallas, Maple Avenue was straightened, and, in the summer of 1923, the remaining abandoned buildings on the property were demolished. But that didn’t spell the end of the famous Gill Well water.

Highland Park’s “Gill Water” Pagoda

Around 1924, “Gill water” tapped from the Glen Rose Strata was made available to Highland Park, via a small “watering house” and drinking fountain on Lakeside Drive (at Lexington), a location which proved to be quite popular. The mineral water was a byproduct of Highland Park’s “deep well” which was drilled in 1924 to tap the pure artesian springs of the Trinity Sands Strata in order to augment the water supply of the City of Highland Park: in order to get down to the Trinity Sands, one had to pass through the Glen Rose Strata — I guess the HP powers-that-be figured they might as well tap the hot mineral water and offer their citizens access to it by building a small fountain and dispensing station. In 1928, the little “watering station” structure was spiffed up with the addition of a tile roof, attractive walkways, and drainage. The photo seen at the top of this post has frequently been misidentified as the Reverchon Park well, but it is actually the Highland Park “pagoda.” Here it is again:

from the book Dallas Rediscovered

from the book Dallas Rediscovered

It can be identified as the Highland Park location because of the photo below from the George W. Cook collection of historic Dallas photos from SMU’s DeGolyer Library — it shows what appears to be a later view of the same pagoda, now slightly overgrown. The steps to the bridge across Exall Lake and the bridge’s railing can be seen at the far right (the bridge led to the Highland Park pumping station, which can be seen on a pre-watering-station 1921 Sanborn map here).

George W. Cook Collection, SMU

George W. Cook Collection, SMU

And, well, there’s the sign that reads “Highland Park Deep Wells — Free to the Public” — here’s a close-up:

(The same sign from the top photo can be seen in a high-contrast close-up here.)

After seeing this photo, I realized that a photo I featured in a post from last year showed the pagoda in what looks like its earliest days, at Lakeside Drive and Lexington Avenue (the bridge can be seen at the left):

eBay

eBay

I was unable to find out when this HP pagoda bit the dust, but the location as seen today on Google Street View is here. (It’s pretty strange to think that a steady stream of people from all over Dallas drove to the Park Cities to fill up jugs with free mineral water; my guess is that the wealthy Lakeside Avenue residents weren’t completely enamored of the situation.)

Reverchon Park Pavilion

Even though the Gill Well Sanitarium Co. had dissolved in 1916, and the last traces of its buildings had been torn down in 1923, the famed well’s water didn’t disappear from the immediate Oak Lawn area. In February of 1925, the City of Dallas opened a $5,000 pavilion, “making up for twenty years indifference to what is said to be the finest medicinal water in the South” (DMN, Feb. 11, 1925). This pet project of Mayor Louis Blaylock seems to have continued to be a place for Dallasites to get their mineral water at least through the 1950s, according to online reminiscences. This 1925 “pavilion” is described thusly in the WPA Dallas Guide and History:

The water, which resembles in many respects the mineral waters of European resorts and is used in several county and city institutions, is carried to the surface in pipes and can be drawn from taps arranged around a semicircle of masonry near the entrance to the park. Here cars stop at all hours of the day and people alight to drink the water or to fill bottles and pails.

I have not been able to find a photograph of that post-sanitarium dispensing site. A 1956-ish aerial photo of Reverchon Park can be found here. I don’t see a “semicircle of masonry” in an area I assume would be located near Maple Avenue and the Katy tracks.

According to a comment on the DHS Archives Phorum discussion group, there was also a public spigot nearer to the original well, along Oak Lawn Avenue, across the street from Dal-Hi/P. C. Cobb stadium.

There is surprisingly little accurate information on the Gill Well online. I hope this overview helps correct some of the misinformation out there. If anyone knows of additional photos of the sanitarium and/or natatorium, please send them my way and I’ll add them to this post. If there are any photos of the Reverchon Park pavilion, I’d love to see those as well. There is a 1926 photo of the Highland Park location which shows two women and two girls filling receptacles — I am unable to post that here, but check the Dallas Morning News archives for the short article “Free Mineral Well Waters Popular” (DMN, May 29, 1926).

**

Incidentally, even though the wells have been capped, that hot mineral water is still there underground and could be tapped at any time. Dallas could still be the “Hot Springs of Texas”!

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo is from p. 199 of Dallas Rediscovered by William L. McDonald. The photo is incorrectly captioned as showing the location of the “Gill Well Bath House and Natatorium, c. 1904” — it is actually the Highland Park dispensing station at Lakeside Drive and Lexington Avenue in about 1928.

“Morning” postcard featuring healthy bathing patrons of the natatorium is from the collection of the Texas Swimming and Diving Hall of Fame and is used with permission.

Photo showing Maple Avenue, pre-straightening, is from the Big D History Facebook page; original source of photo is unknown.

Second photo of the Highland Park Gill Well location (with the vegetation looking a bit more overgrown) is from a postcard captioned “Drinking Bogoda [sic], deep mineral well in Highland Park, Dallas, Texas” — it is from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University; more information on this image is here.

Photo showing Lakeside Drive with the pagoda at the left is a real photo postcard captioned “Lake Side Drive in Highland Park” — it was offered last year on eBay.

Sources of all other clippings, ads, and maps as noted.

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

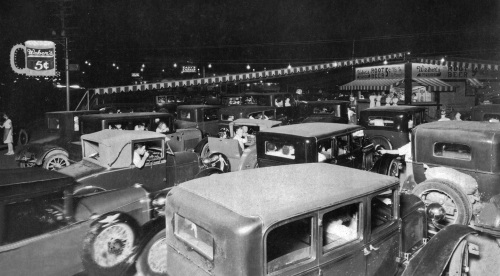

“Senior Cools” at Goff’s… (click for larger image)

“Senior Cools” at Goff’s… (click for larger image)