How To Access Historical Dallas City Directories Online

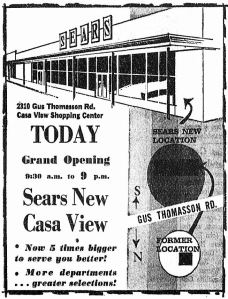

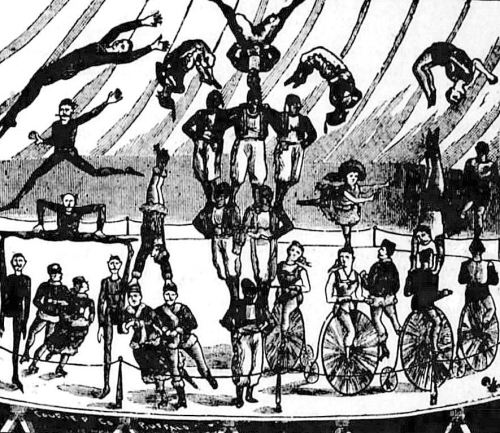

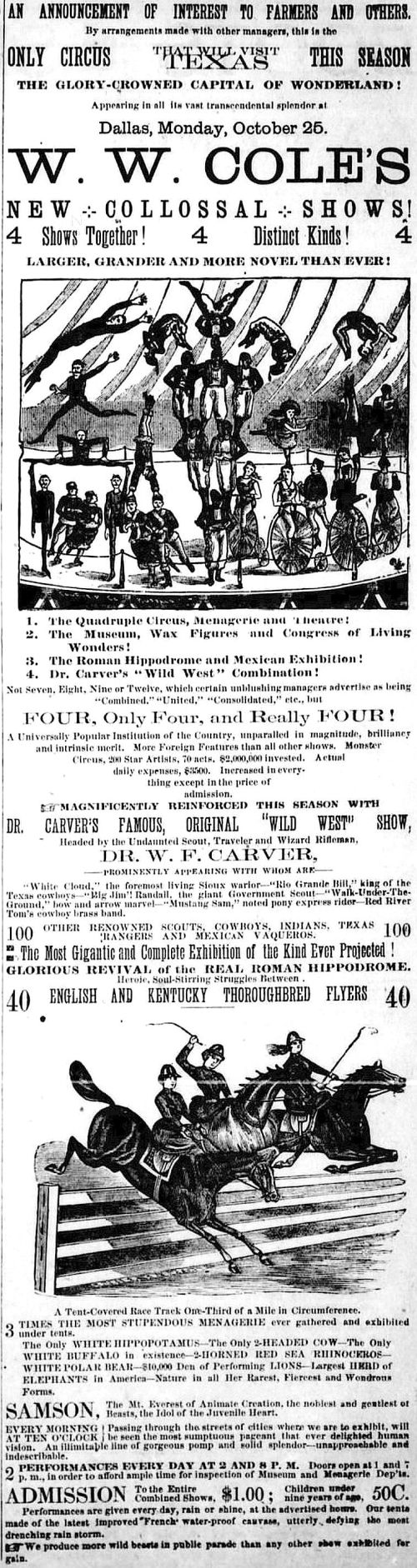

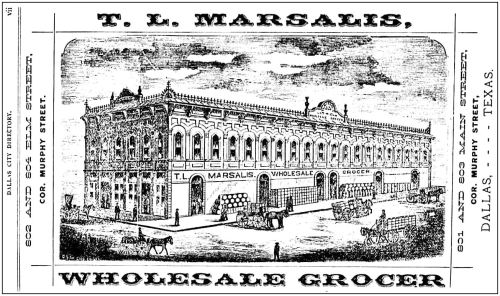

Ad from the 1883 Dallas directory… (click for larger image)

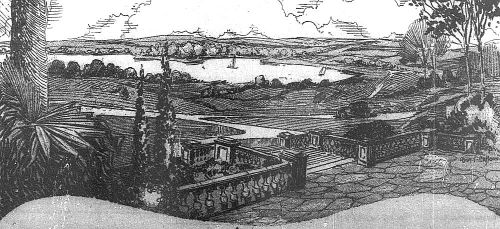

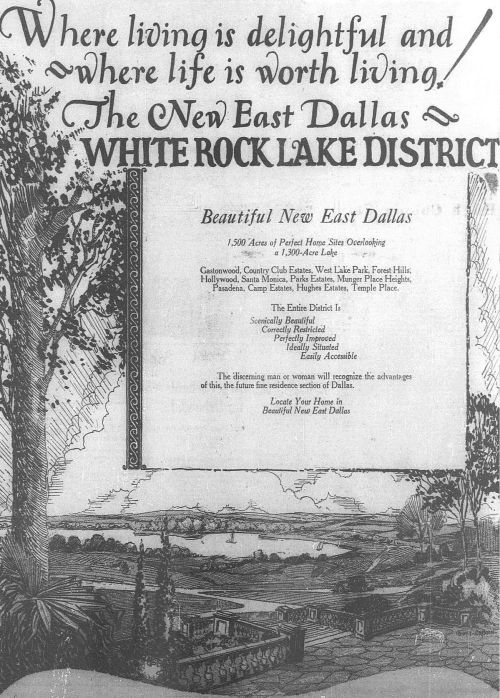

Ad from the 1883 Dallas directory… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

Two of the most important resources I use in delving into Dallas history are newspaper archives and city directories. A couple of years ago I wrote about how to access the indispensable online historical archive of The Dallas Morning News, beginning in 1885 (that post is here), but I haven’t written about how to use the equally important database(s) containing scans of Dallas city directories, beginning with the 1875 directory.

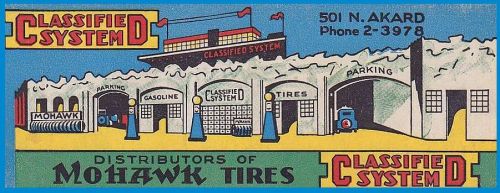

1888-1889 Morrison & Fourmy’s Dallas directory

1888-1889 Morrison & Fourmy’s Dallas directory

There are two ways to do this online: for free, and as part of a subscription (pay) service. I started out by accessing the directories through the Ancestry website, which you have to pay for/subscribe to. It was only recently that I discovered that (as far as I can tell) the exact same directories available on Ancestry are accessible through the Dallas Public Library website — for FREE. All you need is a library card. (You must be a resident of the City of Dallas in order to qualify for a library card. There is more about who can get a library and how one must do this — it requires physically going to a branch with proof of residency — I’ve included this information in that earlier post, here.) (There are a few free online sources which require no library card and no subscription — see those at the bottom of this post.)

Once you have your card and have registered for an account at the Dallas Public Library website, here’s what you do next:

- Log into your account, here

- Click on “DATABASES” at the top

- Scroll down, click on “GENEALOGY”

- Scroll down, click on “HERITAGEQUEST”

- Click on “CITY DIRECTORIES” at the top (you will be able to search through many city directories from around the country, not just the ones from Dallas — and, as you can see, there are all sorts of other interesting databases here, too, such as census records, etc.)

- Enter the name you’re looking for and, voilà.

*

So why are these directories so useful?

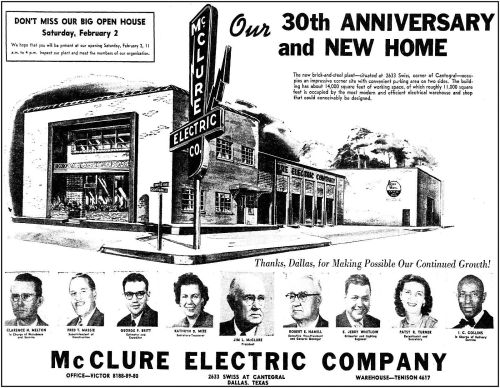

Not only can you determine when someone was living in the city, you can see where they lived, what their occupation was, the name of their spouse, and, in some cases, the race of the person (which, while somewhat disconcerting, can sometimes be quite helpful, especially if the person you are looking for has a common name — up until the ’20s or so, African-American residents and black-owned businesses were followed by “(c)”). (All images shown here are larger when clicked.)

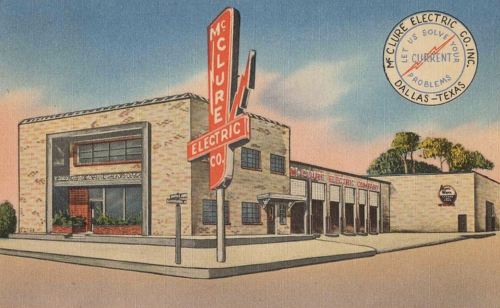

There are also ads, like the one at the top taken from the 1883 directory showing Thomas Marsalis’ wholesale grocery business. Ads are not only interesting, they can contain a lot of information, and, in some cases, a drawing or photograph of the business or proprietor.

1878 C. D. Morrison & Co. directory

Typical business listings look like this:

1891 Morrison & Fourmy’s directory

For me, one of the most useful things I find about these directories is the section containing the street directory. There are city directories covering more than 140 years of Dallas history, and there are a lot of street names you come across in researching a person or a place that no longer exist, have changed names, have the same name as a street in a different part of town (there used to be a lot of street names duplicated in Oak Cliff before it became part of Dallas), etc. These street guides tell you the names of everyone who lived/had businesses on the street (or at least the name of the head of the household or owner of the business), and it gives the names of all cross-streets. An address of 400 Main Street was not in the same location in 1950 as it was in 1900. (See this post on when and why Dallas street numbers changed.) One of the resources I use most is Jim Wheat’s easy-to-navigate list of street names from the 1911 directory (it’s faster and easier to use than one of the actual directories!), with links to the pertinent scanned page — these pages show you not only the 1911 address (which is often the same address used today) but they also show you what the address was BEFORE the number changed. I can’t tell you helpful this has been for me. (See an example here, which shows that before the number changed, 1400 Commerce was 324 Commerce.)

Pages from the 1905 street guide:

One bit of warning: many of the scanned directories that are online are only partial directories — and some years are missing altogether. The directories from the early 1940s, for instance, are a big headache: some have only 20 pages scanned — one wonders why they even bothered. Inevitably, the pages you need (and need badly) are ones that are not available to you, and you will, verily, let fly words your mother would not approve of. Sometimes you can get around the missing data by jumping to the street guide section or the business listings to see if useful info can be found there, but sometimes you are just going to be completely out of luck. This is when a trip to the Dallas Public Library (or possibly just a polite email to an ever-helpful librarian) will help you fill in the blanks, connect the dots, and get that swearing under control. I think they have a complete — or near-complete — set of city directories, either in hard-copy form or on microfilm. (UPDATE: Many of the incomplete directories mentioned above — issued between 1936 and 1943 — are available fully-scanned, for FREE, at the Portal to Texas History. See link at bottom of post.)

You will find so much useful information in these directories that your head will spin. Right off your neck. In a good way. But it’s also just enormous fun to browse them and imagine what the city used to be like in, say, 1889 when that year’s list of the city’s almost 150 saloons looked like this.

***

Sources & Notes

HeritageQuest is the service that provides access to scanned U.S. city directories to libraries across the country (it appears to be the same content the genealogy site Ancestry offers its members). This service is available free to holders of library cards. If you do not live in the City of Dallas, check to see if your local library system subscribes to this HeritageQuest database.

Here are a few other free online sources offering Dallas directory info — and these are available to everyone:

- I’m updating this post on April 5, 2017 to include an INCREDIBLE selection of (from what I can tell) fully-scanned directories — twenty of them! This includes various years between 1902 and 1961 — including most issued between 1936 and 1941 (only partial scans of these editions are available through HeritageQuest/Ancestry, but here we can see complete directories). Thanks to the Dallas Public Library, everyone can access these Dallas city directories at the Portal to Texas History, here.

- Another fully-scanned Dallas directory available online free for everyone can be found on Archive.org: the 1909 Worley’s directory is here.

- Jim Wheat’s Dallas County, Texas Archives has all sorts of incredible stuff on his fantastic site, including links to directory information. Scroll down quite a ways on his main page here, and near the bottom in the left column you’ll see several listings under “Dallas City Directories.” Wheat manually transcribed a lot of these things himself, and those of us who research Dallas history owe the late Mr. Wheat a debt of gratitude. (UPDATE: The entire Roots Web website — not just Jim Wheat’s pages — has been down for several months. One can only hope his hundreds — if not thousands — of hours of work will someday be back online and once again accessible to researchers of Dallas history.)

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.