Elm & Akard, Photographer J. C. Deane, and The Crash at Crush

Yessirree! Elm & Akard, 1936/1937… (click for larger image)

Yessirree! Elm & Akard, 1936/1937… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

One of the best collections of historical Dallas photos — and certainly one of the easiest to access online — can be found in SMU’s DeGolyer Library. I can’t say enough good things about the astounding quality of their vast collection or the willingness to make large scans of their photos available online, free to share, without watermarks (higher resolution images are available for a fee, for publication, etc.). I love you, DeGolyer Library (and all the people and entities behind your impressive digitization process)!

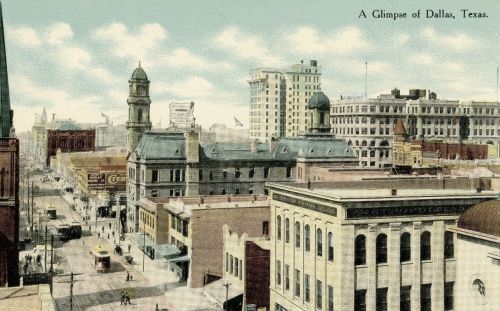

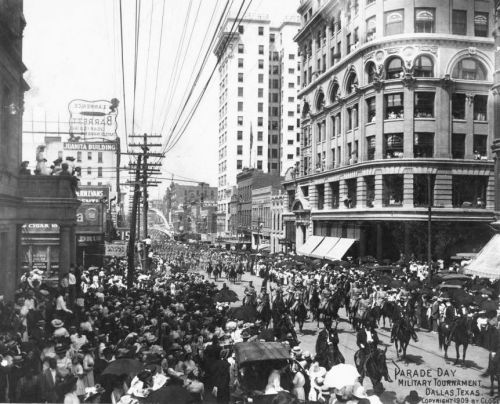

When going through recently uploaded photos, I came across photos from different decades showing the same intersection: the southeast corner of Elm and Akard streets (now the 1500 block). The building appears to be the same in each of the photos, and that is interesting in itself — but I was excited to find a connection in one of them to one of my favorite weird Texas historical events.

And that is the photo below. It’s a cool photo — there’s some sort of parade underway. This is Elm Street looking toward the east (or, I guess, the southeast), and the photographer is just west of Akard Street. At the bottom left of the photo is the United States Coffee & Tea Co. (which I wrote about here); in the background at the right is the Praetorian Building on Main; and just left of center is the Wilson Building addition under construction (which dates this photo to 1911). But the building that interested me the most is the one at the bottom right, the one at the southeast corner of Elm and Akard. I noticed “Deane’s Photo Studio” on the exterior of the upper part of the building. I recognized the name, having seen it on various Dallas portraits over the years, but now I realize there were two photographers named Deane in Dallas in the first half of the 20th century: Granville M. Deane (who had a longer career here) and his brother, Jervis C. Deane — J. C. Deane was the photographer who occupied the upper-floor studio at 334 Elm (later 1502 Elm) between 1906 and 1911. His studio was above T. J. (Jeff) Britton’s drugstore.

Elm Street, looking east from Akard, 1911 (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

Elm Street, looking east from Akard, 1911 (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

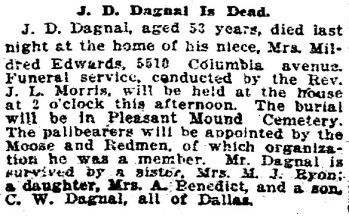

J. C. Deane (born in Virginia in 1860) worked as an award-winning photographer around Texas, based for much of his career in Waco. He was in Dallas only a decade or so, leaving around 1911, after a divorce, noting in ads that he had to sell his business as he was “sick in sanitarium.” After leaving Dallas he bounced around Texas, working as a studio photographer in cities such as Waco and San Antonio. I have been unable to find any information on his death.

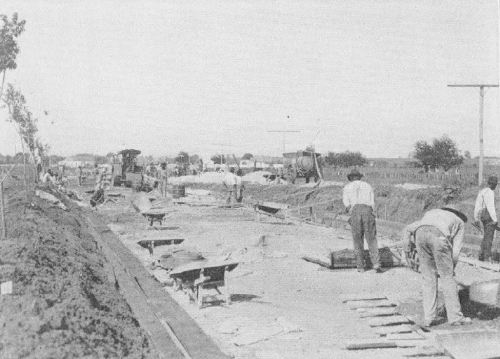

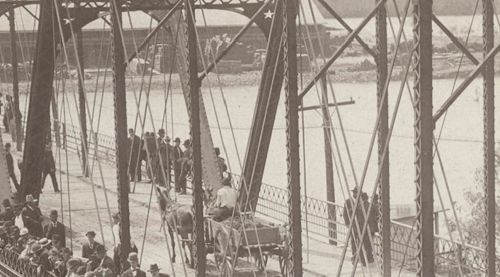

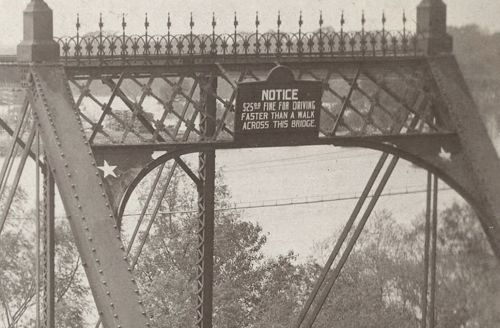

The reason that J. C. Deane holds a place in the annals of weird Texas history? He was one of the photographers commissioned to photograph the supremely bizarre publicity stunt now known as The Crash at Crush, wherein a crowd upwards of 30,000 people gathered in the middle of nowhere, near the tiny town of West, Texas, in September, 1896, to watch the planned head-on collision of two locomotives (read more about this here). Long story short: things did not go as planned, and several people were injured (a couple were killed) when locomotive shrapnel shot into the crowd — one of those badly injured was J. C. Deane who was on a special platform with other photographers. For the sake of the squeamish, I will refrain from the details, but Deane lost his right eye and was apparently known affectionately thereafter as “One Eye Deane.” (For those of you not squeamish, I invite you to read all the gory details, related by Deane’s wife, in an interview with The Dallas Morning News which appeared on October 1, 1896, here.) The photos below are generally credited to Deane, back when he was just good ol’ happy-go-lucky “Two-Eye Jervis.” (All these photos are larger when clicked.) (Scroll down to the bottom of the page for a link to contemporary coverage of the event as reported in The Dallas Morning News.)

I’ve been fascinated by the Crash at Crush ever since I heard about it several years ago, and now I know there’s a Dallas connection — and photos of the building where he worked.

Back to Elm Street.

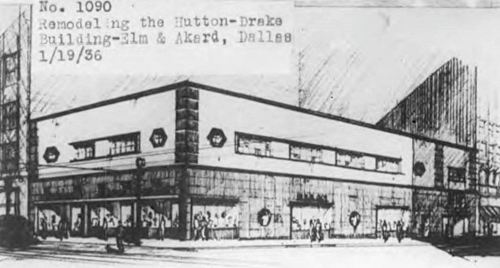

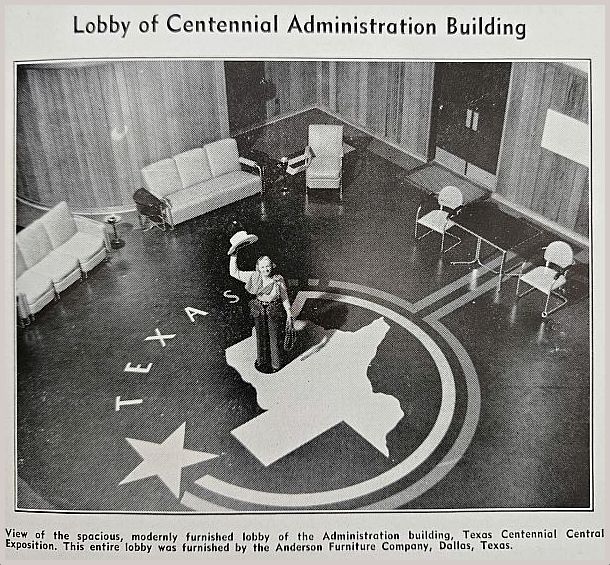

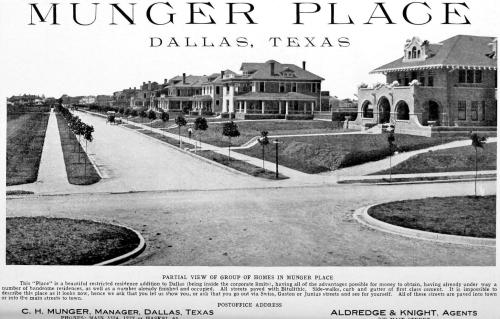

For a brief time (a few months in 1936?) the building was referred to as the “Hutton-Drake Building” and a major renovation of the old building began at the beginning of 1936, when the whole of Dallas was on overdrive to spruce up the city ahead of the crush of Centennial visitors. Here’s an undated “before” photo….

The architect’s drawing of the remodeled Deco delight….

And, because I love this photo so much, here it is again — the finished, revamped building:

Southeast corner of Elm & Akard, 1936/1937, via DeGolyer Library, SMU

Southeast corner of Elm & Akard, 1936/1937, via DeGolyer Library, SMU

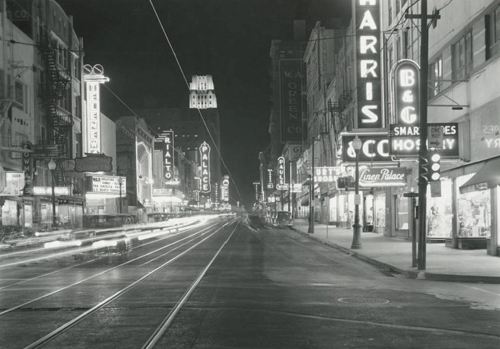

What the heck kind of craziness is this?! I mean I LOVE it, but… it’s very… unusual. I would absolutely never have guessed that this building had been in downtown Dallas. And it appears to be the same building seen in the 1911 photo, just with a very fashion-forward new face. Those little hexagonal windows! Along with that fabulous B & G Hosiery sign, there was a nice little bit of art deco oddness sitting there at the corner of Elm and Akard. The Kirby Building, seen at the far right, seems like a creaky older statesman compared to this overly enthusiastic teenager. The businesses seen here — Ellan’s hat shop, B & G Hosiery, and Berwald’s — were at this corner together only in 1936 and 1937. I could find nothing about this very modern facelift — if anyone knows who the architect is behind this, please let me know! (See a postcard which features a tiny bit of this fabulous building here — if the colors are correct, the building was green and white.)

In November, 1941, Elm Street’s Theater Row welcomed a new occupant, the Telenews theater, which showed only newsreels and short documentaries. By that time the A. Harris Co. had purchased the building at the southeast corner of Elm and Akard and expanded into its upper floors. Telenews opened at the end of 1941 and Linen Palace was gone from this Elm Street location by 1943, dating this photo to 1941 or 1942.

Elm Street, 1941/1942 (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

Elm Street, 1941/1942 (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

All of these are such great photos. Thanks for making them available to us, SMU!

***

Sources & Notes

The three Dallas photos are from the George A. McAfee collection of photographs at the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University — some of the photos in this large and wonderful collection were taken by McAfee, some were merely photos he had personally collected. The top photo (taken by McAfee) is listed on the SMU database with the title “[Looking Southeast, Corner of Elm and Akard, Kirby Building at Right]” — more info on this photo is here. The second photo, “[Looking East on Elm West of Akard / Praetorian Building (Main at Stone) Upper Right Center]” is not attributed to a specific photographer; this photo is listed twice in the SMU database, here and here. The third photo, “[Looking East on Elm from Akard on “Theatre Row” (Including on North Side on Elm from Left to Right — Telenews, Capitol, Rialto, Palace, Tower, Melba and Majestic],” appears to have been taken by McAfee, and it, too, appears twice in the online digital database, here and here. (I’ve updated this post with additional photos from the DeGolyer Library relating to the building’s remodeling in 1936 — links are below the images.)

The three photos from the “Crash at Crush” event are attributed to Jervis C. Deane, and were taken on September 15, 1896 along the MKT railroad line between West and Waco; the images seen above appeared in the Austin American-Statesman on Sept. 16, 1962. More on the Crash at Crush from Wikipedia, here — there is a photo there of the historical marker and, sadly, Jervis Deane’s name is misspelled. Sorry, Jervis!

Read the Dallas Morning News story of the train collision aftermath in the exciting article lumberingly titled “CRUSH COLLISION: The Force of the Blow and Damage Done. Boilers Exploded with Terrific Force, Scattering Fragments of the Wreckage Over a Large Area. The Showers of Missiles Fell on the Photographer’s Platform Almost as Thick as Hail – Description of the Scene,” here.

The southeast corner of Elm and Akard is currently home to a 7-Eleven topped by an exceedingly unattractive parking garage — see the corner on Google Street View here.

There is a handy Flashback Dallas post which has TONS of photos of Akard Street, several of which have this building in it: check out the post “Akard Street Looking South, 1887-2015,” here.

*

Copyright © 2018 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.