The Grand Elm Street Illumination — 1911

by Paula Bosse

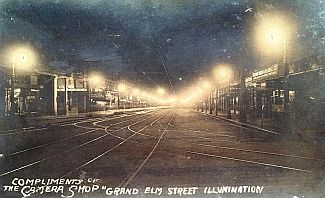

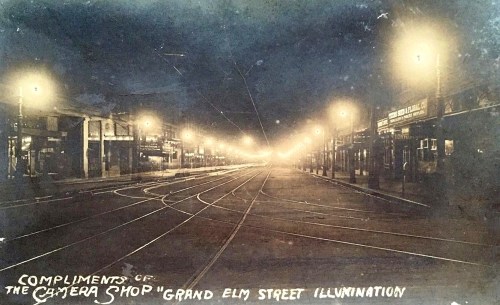

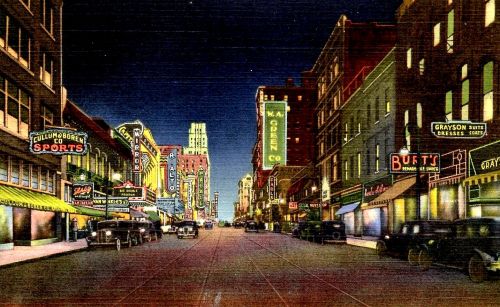

As most of Dallas has now clawed its way back into the world of full electric power after last weekend’s surprise “weather event” (…although, as I write this another big storm is passing through the area), I thought this image might be a timely one. It’s from late 1911 and shows Elm Street with its brand new electric street lights, the installation of which prompted Dallas boosters to dub the street “The Great White Way.” The view is from Ervay, looking west.

1910-1911 was a time of remarkable growth in Dallas. Construction had been started or completed on three important downtown buildings (the Adolphus Hotel, the Southwestern Life Building, and the Butler Brothers building); the historic Oak Cliff viaduct was nearing completion; the dam at the city’s new White Rock reservoir was in operation; and — lo and behold! — ornamental electric street lights (with underground conduits) had been installed along Elm Street, from Market to Harwood.

The buzzword in municipal governments of large American cities at that time was “ornamental street lighting.” What was it? According to The Dallas Morning News:

“Ornamental street lighting” contemplates just what the term signifies. Instead of somewhat indiscriminate and often far from attractive methods of lighting the streets of a city, the adoption of a systematic plan by which, with the placing of uniform lights of pleasing design at regular intervals, a street is not only illuminated, but is ornamented as well. (DMN, Nov. 5, 1910)

The article went on to say that this type of street lighting was an essential element of a progressive and prosperous city (which Dallas most certainly was): not only did it help beautify the city, it also increased property values and helped to decrease crime. …And Dallas leaders really, really wanted it. They just didn’t want to pay for it. Somehow, an agreement was struck in which the cost of the materials, installation, and maintenance of these “ornamental street lights” would be paid for by Elm Street merchants and/or property owners; after one year, the City would take possession of the lights and assume responsibility for their upkeep. Seems like a novel way to fund a city project.

Dallas’ first “ornamental” lights and poles (which, because I like details like this, were painted a soothing olive green) were topped with “bishops’ crooks” (or “shepherd’s crooks”) fashioned in wrought iron, with the lamps suspended from the gooseneck bend. Just over 100 of the magnetite arc lights were installed along Elm, staggered on opposite sides of the street to maximize the illumination’s reach.

The electric lamps will be of a type entirely new in Texas and will give a steady white light that will be more pleasant than the flutter of the common arc light. […] One lamp of 2,000 candlepower will be placed on each pole. (Dallas Morning News, Sept. 14, 1911)

The project was delayed for several months for a variety of reasons (not least of which was the fact that the first shipload of iron poles was mysteriously “lost at sea” as it was en route from New York to Galveston…), but the festive grand unveiling was finally held on September 30, 1911, just in time for Dallas to show off another civic accomplishment to out-of-town visitors who would soon be streaming into town to attend the State Fair of Texas. Dallas’ “Great White Way” thrilled all who beheld it and blazed proudly every night from sunset to midnight. Business owners on Main and Commerce streets were envious of all that fresh, new, well-distributed light over on Elm, and it wasn’t long before those streets had also replaced their garish and old-fashioned, fluttering, stuttering arc lights with the brash new ornamental lights.

Here is a photo of what the lights looked like in December, 1911 (the photo shows the new 12-story Wilson Building annex):

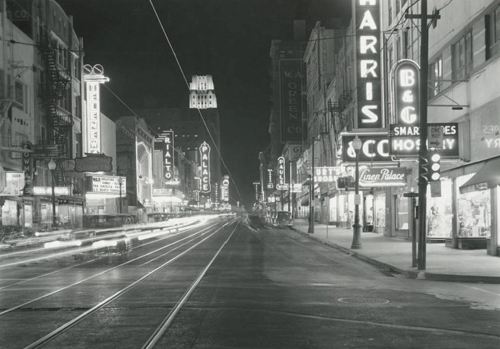

Below are examples of what these street lights looked like a few years after they had been introduced in 1911 (the first two are details of photos from a post found here, and the third one is a detail of a photo taken in front of the Queen Theatre at Elm and Akard in 1914). (UPDATE: I’ve just found a TON of these lamp posts in the historic “Wilson block” area along Swiss Avenue!! See one on Google Street View here.)

*

Read the progress report on the installation of the new lighting system (all images are larger when clicked):

Excited anticipation of the soon-to-be “Great White Way” was building:

Sanger Bros. was one of the many businesses celebrating the arrival of the ornamental lighting. On the day the lights were to debut in downtown Dallas, the department store ran an ad which invited Dallasites to dine in their “lofty” seventh-floor cafe and, afterwards, stroll along the well-lit thoroughfare and soak up the brand new illumination:

Sept. 30, 1911, the night the lights were turned on

Sept. 30, 1911, the night the lights were turned on

Below is the News’ report of the inaugural switch-flipping. (Missing from the article was the fact that someone had been stabbed that night as crowds jostled each other in the streets and along the sidewalks, climaxing with the perp being chased for several blocks before being apprehended; all of this had happened under the glow of the expensive, new, very-bright, law-enforcement-aiding artificial light — that new lighting system was already paying off!)

***

Souces & Notes

Postcard showing “Grand Elm Street Illumination, Compliments of the Camera Shop” is from an old eBay listing. (There is also a copy in the George W. Cook Collection at SMU’s DeGolyer Library, here — you can zoom in a bit more for details, even though, ironically, it’s still pretty difficult to make much out in the shadows. A line from the postcard message reads, “This is a photo of Elm Street at night — pretty swell I think.”)

Businesses seen on the right side of the photo are the Texas Seed & Floral Co. and the Lontos Cafe, which were located near the northwest corner of Elm and Ervay (years later, this was the appoximate site of the Palace Theatre); the Wilson Building (then the Titche-Goettinger department store) is either wholly out of frame at the extreme left, or is only partially visible.

In 1911 — before the ornamental lights were installed — Dallas had something like 1,000 electric (and a few gas) street lights in operation around the city; the arrival of the brighter and more aesthetically appealing Brave New Luminescence of Elm Street’s “Great White Way” spelled the inevitable phasing-out of the old-fashioned arc lights.

Read about how Dallas responded to the 1912 lighting of the Oak Cliff viaduct, the world’s longest concrete bridge, at the bottom of this post.

*

Copyright © 2019 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

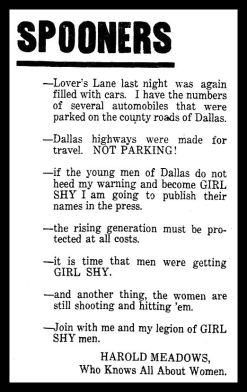

DMN, 1922

DMN, 1922