John W. Smothers’ Tin Shop, Hall & Floyd

Smothers (in car) and employees, ca. 1913

Smothers (in car) and employees, ca. 1913

by Paula Bosse

John W. Smothers (1869-1925) came to Dallas from Huntsville, Missouri around 1890 to begin his career as a “tinner” working for a family friend/in-law, Frank T. Payne. By 1905, Smothers had married a girl from back home, had a child, and had apparently done well enough in the trade to buy a lot on College Ave. (now N. Hall St., in Old East Dallas) where he built his own tin-manufacturing shop, specializing in various sheet metal work.

1909 city directory ad

It looks like this business lasted until about 1918, when Smothers retired and sold the building to his old friend, F. T. Payne. It became a grocery store in 1919. Smothers died in 1925 at the age of 56 — his death certificate lists the cause of death, somewhat alarmingly, as “exhaustion and malnutrition” following a long illness — an extreme case of St. Vitus Dance.

via Ancestry.com

via Ancestry.com

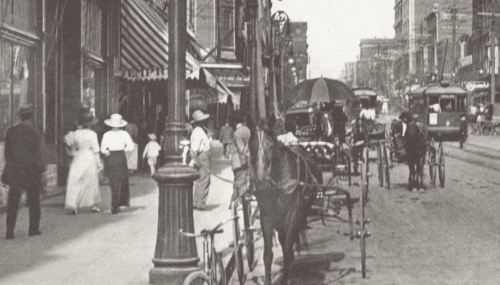

Originally 212 N. College Ave., the address of Smothers’ tin shop became 912 N. College Ave. in 1911 when new addresses were assigned around the city. (See the location of the shop on a 1921 Sanborn map here.) It sat diagonally across the street from Engine Company No. 3, seen below in a photo from about 1901:

Fire station, Gaston & College, ca. 1901

Fire station, Gaston & College, ca. 1901

College Avenue was renamed and became Hall Street around 1946, and the address of the old tin shop building changed again, to 912 N. Hall Street, which is in the area now swallowed up by Baylor Hospital (see what 912 N. Hall looks like now on Google Street View, here).

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo found on eBay. A copy is also in the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University — it can be accessed here. The SMU photo (apparently from the collection of Ralph Smothers, John’s son) has a notation on the back which reads “912 College Ave. <now Hall St.> about 1913 or 14? John Smothers [in car], [James E.] Curly Wilson left, Bob Critcher right.”

Photo of the fire station with the ghostly horse is by Clifton Church and is from the Dallas Fire Department Annual, 1901, which can be viewed in its entirety on the Portal to Texas History, here. (I used this image in my 2016 post “Dallas Fire Stations — 1901.”)

(“Tinner” was not an unusual word to have come across in the early part of the 20th century, but in the 1910 census, the enumerator was either confused or did not understand what was being said, because Smothers’ trade is listed as “tuner” — it looks like the enumerator then just made a weird leap to attempt to explain this and added “piano” under “General Nature of Business,” which Ancestry.com then repeats in its OCR-generated records. That “piano tuner” profession caused me a lot of confusion! To add insult to injury, OCR tells us that his occupation in 1900 was “turner,” and an illegible entry in the 1920 census transforms him into a “retired farmer”! Always approach census record information with a grain of salt — for many, many reasons!)

*

Copyright © 2023 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

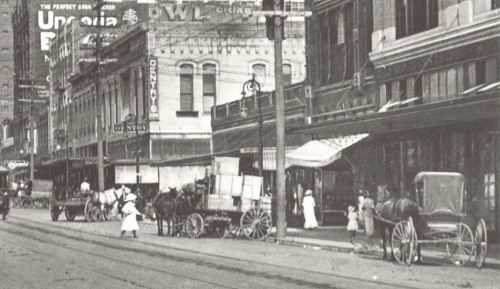

Miami, OK,

Miami, OK,

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU